THE CONTEXT: Introduced in 2013, the National Food Security Act (NFSA) brought about fundamental reforms in the public distribution system (PDS) and most importantly, declared a legal ‘right to food’. The COVID-19 pandemic presented unprecedented challenges to the already vulnerable food security mechanism in India. This article would discuss the nature of issues in PDS/Food security, possible improvements in the delivery of food, and GOI’s steps towards ensuring food security in India, especially in the pandemic and further.

NATIONAL FOOD SECURITY ACT (NFSA)

- Introduced in 2013, the National Food Security Act (NFSA), the largest food-based social safety-net program in the world, covers 800 million individuals (75% of the rural population, and 50% of the urban population) and costs Rs. 4,400 billion (as of 2017).

- Objective: To provide for food and nutritional security in the human life cycle approach, by ensuring access to adequate quantities of quality food at affordable prices to people to live a life with dignity.

- Coverage: 75% of the rural population and up to 50% of the urban population for receiving subsidized foodgrains under the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS).

- The Public Distribution System (PDS) is the apparatus for implementing the NFSA through its nationwide network of fair-price shops (FPS), making highly subsidized foodgrains available to citizens.

- The NFSA categorized households into two groups: NFSA-priority households (NFSA-PHH) and AAY. The allowance of foodgrains was set at 5 kilograms (kg) per person for the PHH category, and 35 kg per household for AAY. Prices were fixed at Rs. 3, 2, and 1 per kg for rice, wheat, and coarse grains, respectively.

- Currently, about 23 crore ration cards have been issued to nearly 80 crore beneficiaries of NFSA in all states and UTs.

NEED FOR FOOD SECURITY IN INDIA

- The latest Global Hunger Index 2020 study does not make for cheery reading for India. The study has placed India 94th out of 107 countries in terms of hunger, locating it in the ‘severe’ hunger category. This puts India alongside the poorest African nations.

- Nearly 47 million or 4 out of 10 children in India do not meet their full human potential because of chronic undernutrition or stunting. India currently has the largest number of undernourished people in the world: around 195 million.

- According to FAO estimates in ‘The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World” report, about 8% of the population is undernourished in India.

- Agricultural productivity in India is sufficient but not on par with the global average: According to World Bank figures, cereal yield in India is estimated to be 2,992 kg per hectare as against 7,318.4 kg per hectare in North America.

FOOD SECURITY

- Food availability: food must be available in sufficient quantities and on a consistent basis. It considers stock and production in a given area and the capacity to bring in food from elsewhere, through trade or aid.

- Food access: people must be able to regularly acquire adequate quantities of food, through purchase, home production, barter, gifts, borrowing, or food aid.

- Food utilization: Consumed food must have a positive nutritional impact on people. It entails cooking, storage and hygiene practices, individuals’ health, water and sanitation, feeding and sharing practices within the household.

REASONS FOR POOR FOOD SECURITY STATUS IN INDIA

Poor Maternal health:

- South Asian babies show very high levels of wasting very early in their lives, within the first six months. This reflects the poor state of maternal health.

- Almost 42% of adolescent girls aged 15 to 19 have a low body mass index (BMI), while 54% have anemia.

- Almost 27% of girls are married before they reach the legal age of 18 years, and 8% of adolescents have begun childbearing in their teens.

- Almost half of all women have no access to any sort of contraception.

Poor sanitation:

- Poor sanitation, leading to diarrhea, is another major cause of child wasting and stunting. At the time of the last NFHS, almost 40% of households were still practicing open defecation.

Poverty:

- International Food Policy Research Institute’s recent findings say that three out of four rural Indians cannot afford a balanced, nutritious diet.

- The emaciated rural livelihoods sector and lack of income opportunities other than the farm sector have contributed heavily to the growing joblessness in rural areas. (The Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2017-18 revealed that rural unemployment stood at a concerning 6.1 percent, which was the highest since 1972-73.)

- The existing deprivation has been aggravated by the pandemic, with food inflation. This has adverse effects on their capacity to buy adequate food.

Dietary habits:

- Indian diets typically involve copious consumption of staples such as rice and wheat, with limited dietary diversification toward micronutrient-rich foods like fruits, vegetables, and animal products.

- “Hidden hunger,” or micronutrient deficiency, that inhibits proper growth and development of the human mind and body, affects a large section of the Indian population.

Policy failures:

- The national food security approach has been hung up in a ‘defeat the famine’ mode, which aims to provide gross calorie availability via the National Food Security Act (NFSA).

- The MGNREGS continue to be the lone rural job program that, too, had been weakened over the years through great delays in payments and non-payments, low wages, and reduced scope of employment.

- The public distribution system (PDS) fair price shops often fail to function due to supply delays.

- While this stable and subsidized policy has helped counter the problem of absolute hunger, it limits the food choices and does not provide the needed nutrients and micro-nutrients.

THE NATIONAL FOOD SECURITY ACT (NFSA) & PDS DURING COVID-19

Providing food to all:

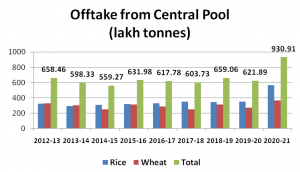

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, PDS was entrusted with meeting the food security needs, expanding its portfolio, and providing free grains.

Government support during Covid-19 pandemic

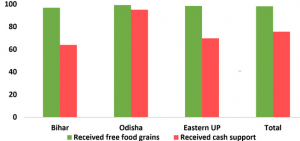

- In March 2020, the government announced free foodgrains and cash payments to women, senior citizens, and farmers as part of the PMGKY. According to various estimates, an overwhelming 98% did receive free foodgrains, that is, 5 kg rice or wheat and 1 kg pulses. However, in numerous cases, household members had been left unaccounted for in the PDS food relief, which is important when there is per capita allotment.

- On May 14th, 2020, Finance Minister stated that 100 percent of ration cardholders will be covered in the One Nation One Ration Card scheme by March 2021. In the present system, a ration cardholder can buy food grains only from a Fair Price Shops (FPS) that has been assigned to her in the locality in which she lives. However, under the ‘One Nation, One Ration Card’ system, the beneficiary will be able to buy subsidized food grains from any FPS across the country.

CHALLENGES NATIONAL FOOD SECURITY ACT (NFSA) & PDS

Limited access to ration cards:

- The delay in the rollout of NFSA cards was due to a delay in incorporating the 2011 Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) for the selection of eligible households, exclusion errors, and widespread lack of awareness about NFSA provisions and eligibility requirements.

- Those in charge of this paperwork were under-informed and not capable of discharging these responsibilities efficiently. Moreover, with the transition to per-capita entitlements, regular, and reliable updating of ration cards became necessary and this proved cumbersome.

Quantity and price of foodgrains:

- With per-capita entitlement, bigger families gained in terms of the number of grains received while smaller families lost out. Even after 8 years since the introduction of the NFSA, many remain unaware of specific entitlements, both in terms of quantity and price (30% in Bihar, 22% in East UP, and 17% in Odisha).

- Unaware households are prone to entitlement snatching and lower fetching of entitlements. These beneficiaries report lower quantities or higher prices than mandated.

Gaps in food delivery:

- Over the years, the PDS delivery system has been known to be susceptible to leakages due to maladministration and, in some cases, outright theft.

- Pre-NFSA, beneficiaries stated that they had faced the problem of long waiting times at FPS, no electronic weighing machines (EWM), inferior grain quality, and delayed opening of FPS.

Recent issues:

Issues during Pandemic:

- One primary issue is that ON-ORC requires a complex technology backbone that brings over 750 million beneficiaries, 5,33,000 ration shops, and 54 million tonnes of food grain annually on a single platform.

- The government was also unable to honour the ‘pulse of choice’ pledge because of supply constraints.

Tweaking the NFSA:

- NITI Aayog, through a discussion paper, has recommended reducing the rural and urban coverage under the National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013, to 60% and 40%, respectively.

- It has also proposed a revision of beneficiaries as per the latest population which is currently being done through Census- 2011. In the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, it will be a double burden (Unemployment and Food insecurity issues) on the poor sections of the society.

NATIONAL FOOD SECURITY ACT (NFSA) & PDS: THE WAY FORWARD

- Learning from other low-income societies with successful micro-nutrient-based interventions, we need to redefine the scope and mechanism of the PDS programs to extend beyond funneling cheap or free grains and generate higher fidelity using the vast local network.

- Promising lessons can be seen in Mexico’s distribution system of nutrition pouches and the SMS-based digital PDS in the Indian state of Chhattisgarh where the distribution involves pulses and millets in addition to rice and salt.

- Focusing on EUP, Bihar, and Odisha, we study PDS in the post-NFSA scenario. There is evidence of some positive movements like coverage of households, but there is considerable scope for improvement in other areas. There are areas beyond prices and quantities of grains that need to be addressed, such as the quality, variety of grains, and quality of services at FPS, that result in differential access even post-NFSA.

- The differential experiences with PDS are not accidental and are likely a result of poor design, and a lack of sensitivity to the demand side of the programs in keeping with community needs and preferences. Thus, more targeted and inclusive penetration is desired which can be achieved with the cooperative efforts of state governments and local NGOs.

THE CONCLUSION: During Covid-19, PDS seems to have delivered but issues with eligibility and lack of commodity choices remain even with the NFSA. One overlooked advantage of the PDS is how it helps shelter households from price risk when prices are high, the value of the in-kind transfer of rice is also higher. Thus, in the Indian case, the NFSA cannot be tweaked against the favour of vulnerable sections. NFSA combined with the PDS, end hunger, achieve food security and improve nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture (SDG 2), hence the effective implementation of these schemes becomes even more crucial in the COVID-19 aftermath.

Spread the Word