The Context: Amid widespread economic disruptions caused by Covid 19 pandemic, the discussions on Universal Basic Income (UBI) and its forms have gained momentum. Recently, NHRC had informed UNHRC that the idea of UBI is being actively considered by the Union government. UNDP, in a recent report, recommended immediate introduction of a Temporary Basic Income for the world’s poorest so that people could stay at home amidst rising number of cases.

What is UBI?

- According to Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN), “A basic income (BI) is a periodic cash payment unconditionally delivered to all on an individual basis, without means-test or work requirement.” (A means test determines eligibility of a person or household to receive welfare benefits)

- Basic income (BI) is a fixed income an adult receives from government by the virtue of being citizen. It is “basic” because it is just enough to provide for basic consumption and income security. The idea is that a society should look out for its people’s survival.

- UBI has three components: universality, unconditionality, and agency(by providing support in the form of cash transfers to respect, not dictate, recipients’ choices).

What are different forms of UBI?

- Forms vary on the funding proposal, the level of payment, the frequency of payment, and the particular policies proposed around it.

- Each of the parameters (a universal, unconditional, individual, regular and cash payment) is fundamental.

- In Indian discussions, the term is frequently used but most discussions revolve around some sort of a Quasi UBI which is based on exclusion rather than inclusion criteria. (The rich are excluded rather than including the poor).

- A Guaranteed Basic Income is a guaranteed, non-universal income transfer to the poor which is enough to provide for their basic needs. Its only difference with UBI is ‘universality’.

Defining characteristics of UBI

- Periodic

- Cash payment

- Universal

- Individual

- Unconditional

DIFFERENT UBI PROPOSALS

Universal Basic Income (UBI)

An unconditional cash transfer to all residents in a country.

Guaranteed Minimum Income (GMI)

A social assistance means-tested scheme similar to UBI but targeted to the poor.

Quasi Universal Basic Rural Income (QUBRI)

Proposed by Arvind Subramanian, to tackle the agrarian and rural distress in India. 75% of the rural population (farmers and non-farmers) can be covered by not targeting IN the deserving poor but excluding OUT the demonstrably non-poor. It is advocated as a more effective policy than MSP and loan waivers.

Partial Basic Income (PBI)

Any income guarantee set at a level that is less than enough to meet a person’s basic needs.

Negative Income Tax (NIT)

Proposed by Milton Friedman. It is an income support payment for individuals with no income. The amount reduces with increasing income. Break-even point is fixed at a certain level of income and after that point taxes start.

IS THIS A NEW IDEA?

- The idea was first suggested by Sir Thomas More in 16th century and in 1970s, it was advocated by free-market economists such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman.

- ‘Industry 4.0’ may permanently reduce the demand for labour leading to job losses, stagnant incomes and worsening inequality.

- Previously, technological developments mostly affected less skilled workers which required greater investment in education and skilling.

- The fears are that new digital technology is also destroying higher-skilled, better-paid jobs.

- Hence it will no longer be possible for governments to deal with unemployment, insecure work and stagnant incomes by usual measures.

- In India a Planning Commission study of 1962 led by Pitambar Pant analysed how every citizen could be guaranteed a minimum standard of living by 1977.

- The idea was discussed by the 2016-17 Economic Survey. It was part of manifesto of Congress Party (NYAY) in 2019 Lok Sabha elections.

- Basic income has moved into the mainstream of public debate in contemporary times mainly as a a response to two concerns which aggravate each other:

- Structural changes in the global economy – low wages and insecure employment with increasing the mobility of capital and increasing incomes from ownership of capital resulting in high inequalities. Thomas Piketty and Oxfam have drawn attention to this.

- ‘Industry 4.0’ and associated technological changes are expected to worsen these problems especially in developing countries.

- UBI is argued to be a better and efficient policy alternative to combat poverty, rising inequalities and unemployment.

- Its advocates range across the ideological spectrum. It is by both developed and developing countries for reasons which are briefly discussed in the table below.

JUSTIFICATIONS FOR DEVELOPED AND DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

DEVELOPED COUNTRIES

- Ageing population, stagnant median incomes, demand slump

- Increased automation (industrial revolution 4.0), rise of gig economy and job insecurity

DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

- Poverty alleviation

- Failure of trickle down model

- Reduction of market distortion caused by government subsidies

- Administrative efficiency

How the context of present discussions is different?

- Covid‐19 presents the need for rapid and immediate relief. An income support can provide immediate help due to its design simplicity.

- Growth Contraction – Global growth is projected to be -4.9% (IMF, WEO, June update) in 2020. India’s GDP growth is projected at -4.5% (IMF, WEO, June update), lowest since 1961.

- Unemployment – the lockdown may push almost 40 crore people into poverty (ILO). Unemployment, already at a 45-year high in 2018, will only rise post-Covid-19. Even if there is a faster recovery, employment growth will take longer to recover.

- Large unorganized sector – Almost 90% of India’s workforce is in the informal sector characterized by less than minimum wages and no social security. This sector has also witnessed widespread job losses. Present schemes serve only pre-existing set of beneficiaries and a large number of deserving individuals are left out.

- The economic consequences of the virus will remain for several months ahead. Governments around the world are considering income transfers to ensure basic sustenance for the poor and vulnerable groups and boost domestic demand, at least till the economy normalises.

What is the case for Basic Income?

A) Social Justice

- UBI promotes a just and non-exploitative society.

- A society that fails to guarantee a decent minimum income to all citizens will fail the test of justice (John Rawls).

- UBI respects all individuals as free and equal. It promotes liberty because it is anti-paternalistic.

- It also promotes equality by reducing poverty.

B) Poverty Reduction

- A Basic Income may be the fastest way of reducing poverty.

- UBI is also more feasible in a low middle income country like India, as relatively low levels of guaranteed income can yield immense welfare gains.

- Such a scheme can address intra-household poverty and vulnerable sections such as small and marginal farmers, informal and low skilled workers and women.

- It can also act as a safety net against events like sudden job losses, income shocks and health issues which can trap individuals into poverty.

C) Agency

- The current welfare system reduces dignity of the poor by assuming that they cannot take correct economic decisions.

- As different individuals face different dimensions of poverty, the state is not in the best position to take economic decisions for them.

- BI releases citizens from paternalistic and clientelistic relationships with the state. A basic income treats them as active agents, not passive recipients.

D) Employment

- BI can provide minimum income security in an era of uncertain employment generation.

- It can create flexible and non-exploitative labour markets since individuals will no longer be forced to accept unjust working conditions for subsistence.

- It would not result in withdrawal of beneficiaries from the labour force if the income support is not too large.

- In fact, it can promote employment and economic activities as extra income can be used as interest-free working capital.

- While programmes like MNREGS lock up beneficiaries in low-productivity work, income support will provide them the opportunity for skilling and better employment options.

E) Administrative Efficiency:

- Existing welfare schemes suffer from defects like misallocation, leakages and exclusion errors.

- When the JAM trinity is fully adopted, a more administratively efficient mode of welfare delivery can be implemented.

- An income support scheme is better due to its in-built simplicity. (Abhijit Banerjee)

F) Alleviating rural distress

- LPG reforms have largely passed agriculture, rural India and the poor. This has resulted in agrarian and rural distress.

- The latest NSS All India Debt and Investment Survey (2013) show over 70% rural population is indebted.

- The poor borrow to meet consumption as well as contingency needs and rarely for productive purposes. They rarely accumulate assets.

- A guaranteed income transfer will reduce their vulnerability, boost rural demand without affecting labour-supply.

WHAT IS THE CASE AGAINST BASIC INCOME?

A) Reduces the incentive to work

- An income guarantee will discourage potential workers.

- Necessity is one of the dominant motivations for work without which workers will choose leisure over work.

- It has potential to create labour market distortions by affecting labour mobility like MGNREGA.

- But a minimal level of income support is unlikely to be a disincentive to work.

- Basic income is not meant to replace employment. One cannot live entirely on basic income.

B) Should income be detached from employment?

- Traditionally income and employment have been aligned in most societies

- But, society already delinks income from employment the rich and privileged in the form of inheritance or non-work related income.

C) Reciprocity

- Society is a “scheme of social cooperation” and income should be conditional to individual’s contribution to society (eg MNREGS and Food for Work programmes)

- But, social objectives dictate to create a society where extreme poverty doesn’t exist.

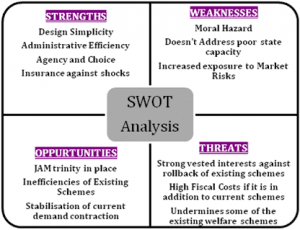

A Brief Summary of arguments

Favour

- Poverty and vulnerability reduction

- Choice and Agency

- Better targeting (inclusion) of poor.

- Insurance against income and other shocks.

- Improved financial inclusion due to greater usage of bank accounts and higher profits for banking correspondents (BC). Access to credit will improve due to increased incomes.

- Psychological benefits

- Administrative efficiency

Against

- Conspicuous and wasteful spending.

- Moral hazard (reduction in labour supply)

- Increased gender disparity as men are likely to exercise control over spending.

- Difficult implementation due to the current status of financial inclusion among the poor.

- High fiscal cost given political economy of exit. It may become difficult for the government to withdraw the scheme in case of failure.

- Opposition may arise from inclusion of rich individuals.

- Exposure to market risks (cash vs. food)

What is the evidence from empirical studies?

Various pilots and experiments have been conducted. Two of them are discussed below:

India

A pilot project conducted between 2010 and 2013, by SEWA, UNICEF and UNDP covering 6,000 beneficiaries in Delhi and Madhya Pradesh.

Findings

- An unconditional income support was not a major disincentive to work.

- Beneficiaries became more productive as they shifted from wage labour to own cultivation which resulted in increased agricultural production and land cultivated.

- Improved nutritional uptake, school enrolment and attendance of female students and reduced incidence of indebtedness were observed.

- No statistical evidence of any increase in economic “bads” such as consumption of alcohol and tobacco.

- The study also shows that a right amount as a basic income has disproportionately higher positive effect than the monetary value.

Finland

Introduced its version of the UBI in 2017 as a social-welfare experiment for the unemployed section of society with roughly $600 every month as financial aid.

Findings

- Beneficiaries enjoyed greater financial security and mental health but there was no disincentive to work.

- They were free to do work they found meaningful, they were more able to take flexible but insecure opportunities

- But the trials have been inconclusive, showing psychological improvements among recipients but limited success in achieving economic or social objectives.

Recently, the Spanish government has decided to implement a national minimum income. People in around 1 million low-income households will get roughly $500 a month in income. The plan aims to reach 2.3 million people, and is expected to cost the government about 3 billion euros a year.

How a Basic Income Scheme is better than in-kind schemes?

A) What are the drawbacks of existing schemes?

- Large number of schemes – The Union government runs about 950 central sector and centrally sponsored sub-schemes accounting for about 5% of the GDP.Besides, most of the central sector schemes were ongoing for at least 15 years and 50% of them were over 25 years old. (Economic Survey 2015-16)

- Misallocation of resources across districts – The poorest districts receive a lower share of government resources when compared to their richer counterparts. The backward districts together accounts for 40% of the poor but receive 33% of the resources.

- Exclusion of genuine beneficiaries – Misallocation would mean that then some genuine beneficiaries would be excluded. For instance, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Orissa and Uttar Pradesh account for over 50% of the poor in the country but access only a third of the resources spent on the MGNREGS in 2015-16.

B) How can income transfers overcome these Issues?

a) Misallocation

- The UBI, by design, should effectively tackle issues related to misallocation.

- The simplicity of the process also implies that the success of a UBI depends much less on local bureaucratic ability than other schemes.

b) Out of system leakage

- Could be reduced as direct transfers are made to the beneficiaries’ bank accounts.

- Since discretionary powers of authorities are eliminated almost wholly, the scope for diversion is reduced considerably.

c) Exclusion error

- Given the link between misallocation and exclusion errors, exclusion errors should be automatically reduced.

- Due to expanded coverage, exclusion errors under the scheme should be lower than existing targeted schemes.

- Most of these schemes are non-universal targeted programmes whose main problem is identification.

- Narrowly-targeted programmes are prone to exclusion and inclusion errors out of system leakages.

The core arguments over a universal basic income remain but Covid 19 pandemic makes a case for emergency temporary income payments targeted at the poor.

How the poor can be targeted?

- India’s record of targeting has been poor with evidences of data manipulation and corruption, exclusion of the poor and leakages to the rich. Targeting was both inefficient and inequitable.

- Recognizing this, individual states- like Tamil Nadu and Chhattisgarh – universalized the PDS and a few other government schemes. The NFSA (2013) also mandated access to the PDS to nearly 70% of all households, choosing to exclude only the identifiably well-off.

- Empirical evidence suggests that the higher the coverage, the lower the leakages. Thus there is a gradual move towards greater inclusion error in order to avoid exclusion issues.

- But if basic public services are maintained, there is limited fiscal space for direct income support. It will have to be limited to some extent. Instead of targeting IN the poor, demonstrably well off should be targeted OUT.

- Datasets like SECC, 2011 can be used. It can be complemented by other datasets like the Agriculture Census, 2015-16 (small and marginal farmers), MGNREGA rolls from 2019 and those covered by Jan Arogya and Ujjwala schemes. Aadhaar can be used to rule out duplications.

- But none of these lists are perfect. The priority should be to err on the side of being inclusive.

Where is the fiscal space to finance a BI scheme?

- Indian economy was struggling even before the Covid-19 crisis. The fiscal deficit was already higher (4.6% of the GDP) than the limit prescribed by the FRBM Act (3.8%). Due to economic slowdown, revenue collection will also be certainly lowered this fiscal.

- Yet most observers have argued that in these extraordinary circumstances, if India believes that a basic income is required, then it should be able to find the money for it.

- Former Chief Economic Adviser Arvind Subramanian has suggested various measures to create the fiscal space like reallocation of budget outlays, external borrowing, issuing government bonds and direct monetization of government deficit (having the Reserve Bank “print money” in exchange for government bonds).

- An analysis of budgetary allocations revealed that reduction of allocation by half to 11 departments, such as the election commission, department of posts etc could free up funds up to about 1% of the GDP.

ILO Recommended Financing Mechanisms

- Re-allocating public expenditures

- Increasing tax revenues

- Lobbying for aid and transfers

- Eliminating illicit financial flows

- Using fiscal and central bank foreign exchange reserves

- Restructuring existing debt

a) Streamlining inefficient subsidies

- Fiscal space for a basic income scheme can be created by streamlining and removing some extremely inefficient and difficult–to-remove middle class subsidies like the subsidy to Air India and fertilizer subsidy (Abhijit Banerjee)

- Estimates by NIPFP suggest that subsidies (central plus state) that mainly go to better-off people (‘non-merit subsidies’) amount to about 5% of GDP. The Economic Survey 2016-17 estimates that central subsidies for the non-poor/middle class households are equivalent to about 1% of GDP.

- A basic income should be additional to the poor’s existing consumption which includes consumption from public programs (PDS, MNREGA, etc.).

- Healthcare, education, water conservation and other merit subsidies should not be reduced to fund income transfers as these are meant for long-term improvement in human development.

b) Taxation

- ‘Revenues foregone’ (primarily tax concessions to companies) in the Union Budget are about 6% of GDP (2014-15 actuals). At least one-third of these revenues foregone can be made available.

- There is also scope for more taxation. India has a low tax-to-gdp ratio (around 10.6%) which is substantially lower than in China, Brazil and some other developing countries.

- Arvind Subramanian argues for redistributive equality for financing a basic income scheme by relying on a wealth tax of 1.5% for billionaires, a tax on properties worth more than Rs 1 crore and eliminating some “middle class subsidies”.

c) Merger of existing schemes

- The top 10 centrally sponsored or central sector schemes (not including subsidies) cost about 1.4% of GDP (2014-15 actuals) and the remaining 940-odd sub-schemes account for 2.3%.

- Many of these schemes have overlapping objectives and can be merged.

- Some resources may also be released by terminating some of the wasteful welfare programmes, but programmes like ICDS, mid-day meals, and MGNREGA should not be replaced.

d) State’s contribution

- The Central and state governments should work together because the Centre can provide resources more easily while the states will have a critical role in implementation.

- Initially, a minimum UBI can be funded wholly by the centre.

- The centre can then adopt a matching grant system wherein the centre’s contribution is equal to the state’s contribution.

While the fiscal space exists for a basic income scheme, the government will have to decide what expenditures to prioritize. Though BI may seem to be an attractive policy option, it should not take over the fiscal space for a well-functioning state. As the present crisis will persist for some time, former RBI Governor Urjit Patel has advocated that the government should keep some fiscal space open. At the same time adequate funding should be made available to help those suffering from severe deprivation.

How should an UBI should be designed and implemented?

The design should incorporate lessons learned through pilots and other experiments. It should consider the following constraints and guiding principles.

Constraints

- maximum possible coverage but no strict universality

- containing fiscal costs

- difficulty of exit from existing programmes

- the implementation capability of the Indian state

Guiding Principles

- De jure universality, de facto quasi-universality – to reduce the powerful resistance and high fiscal costs produced by complete universality, the scheme should approach targeting from an exclusion of the non-deserving perspective than the current inclusion of the deserving perspective.

- Gradualism – the UBI must be embraced in a deliberate, phased manner, weighing the costs and benefits at every step.

Schemes similar to UBI in India

- National Social Assistance Programme

- DBT for various scholarships and LPG subsidy

- PM Garib Kalyan package

- PM-KISAN

- Rythu Bandhu

- KALIA

- Rythu Bharosa

Considering the above some of the probable approaches are mentioned below:

- Start by offering UBI as a choice to beneficiaries of existing programs.

- UBI for women – Empirical evidence shows the higher social benefits and the multi-generational impact by investing in women.

- Universalize across groups – Basic Income first for certain vulnerable groups – widows, pregnant mothers, the old and the infirm.

- Redistributive resource transfers to states – A part of the redistributive resource transfers may be transferred by the centre directly into beneficiaries’ accounts.

- UBI in urban areas – These areas are less likely to suffer from poor banking infrastructure and lack of individuals with bank accounts.

Prerequisites for Success: JAM

- Effective financial inclusion and expansion of banking infrastructure is crucial for the success of basic income scheme.

- To reduce leakages a transparent and safe financial architecture that is accessible to all is required which can be provided by JAM.

- Success of the BI depends on the success of JAM.

How should UBI be determined?

- The 2016-17 Economic Survey calculated an income of Rs 7620/ individual/year based on the 2011-12 poverty estimates (Suresh Tendulkar).

- As the methodology adopted by the Suresh Tendulkar committee faced severe criticisms, there is a need to reassess what constitutes the minimum consumption basket.

- Although there is no universal principle of determination but a target a transfer should represent about 1/3rd of the current consumption of the poorest 40%.

- Income transfers can have various slabs as per multiplicity of deprivations and degree of vulnerability (as per SECC data).

- As Abhijit Banerjee has argued, the key is to create fiscal space first.

How to shield the income transfers from politics and inflation?

- To protect the ‘real’ value of cash transfers from inflation it should be revised periodically by indexing it to CPI.

- A politically neutral mechanism should be created to insulate the amount from blowing up due to competitive politics. For this income transfers could be set as a constant proportion of GDP.

- Alternatively, a special fund financed on a permanent basis from wealth and property taxes and the revenues from elimination of middle class subsidies can be created. (Subramanian)

What are the implementation challenges and concerns?

A) Financial Inclusion

- Financial inclusion in India has progressed substantially since the PMJDY but still nearly 1/3rd of adults, mostly women, SCs, STs and elderly still do not have a bank account.

- Researchers have found that 53% of poor women in India don’t have PMJDY account.

- Last mile concerns – In a majority of states people are 3-5 km away from any form of access point (bank branches, ATMs and BCs). 26% of poor women live more than 5 km away from their nearest banking point

- In terms of JAM preparedness, considerable ground has been covered, but there is quite some way to go.

- Independent evaluations of the pilot exercises of DBT in lieu of PDS in Chandigarh and Pondicherry emphasize the need for an improved digital financial infrastructure.

B) High Fiscal Costs

- Cash transfers offering even poverty-line income are estimated to cost around 10% of GDP.

- In theory, non-merit subsidies could be abolished but in practice, this is politically unlikely. Therefore cash transfers may be over and above current expenditure.

- Also, the fiscal deficit has already breached the limit and government revenues are expected to decline sharply this fiscal.

- Additional borrowing can be counter-productive as higher fiscal deficit will fuel inflation which will hurt the poor the most.

C) Political challenges

- Vested interests against replacing existing welfare programmes are too strong.

- Once implemented, competitive politics will ensure the continuation of schemes like BI, even if it fails.

- Electoral competition will push the amount of BI further at the risk of fiscal imbalance.

D) Authentication errors

- While Aadhar is designed to solve the identification problem, it cannot, on its own, solve the targeting problem.

- While Aadhaar coverage has improved but some states report authentication failures: 49% failure rates are estimated for Jharkhand which has led to starvation deaths.

- Failure to identify genuine beneficiaries result will in exclusion errors.

E) Supply side and capacity problems

- A basic income can address the problems of demand and purchasing power, but not supply-side and capacity problems.

- Without addressing supply-side bottlenecks, income support will be inflationary.

- But inflationary pressures may trigger a virtuous cycle with entrepreneurs responding to the assured demand.

F) Leakages

- While evidence supports universalization of in-kind transfers reduced leakages in India, it is not clear if a cash transfer will necessarily result in lower leakages.

- Due to very large amount of cash flowing through the system, there could be a perverse incentive resulting in greater corruption.

- It is an open question if a basic income today will necessarily work better than simply universalizing other in-kind transfers it tends to replace.

Way Forward

Basic income may be a good idea which can lead to improved health and educational outcomes and a more productive workforce. But it is untested anywhere with India’s level of income disparity and inequality. There is need for good large scale pilots of sufficient time to generate empirical evidence.

At the same time, basic income system is not a substitute for state capacity; it is a way of ensuring that state welfare transfers are more efficient. In the long run, state capacity needs to be enhanced to provide a whole range of public goods. State institutions must be strengthened to deliver the universal basic services (7 core services: health care; education; shelter; food; transport; legal and democracy; and information – which should be available to all citizens regardless of their ability to pay) and to regulate delivery of services by the private sector. Direct transfers should not be at the expense of these services.

BI should not decrease the incentive for real reforms like land and labour reforms, justice system reforms, logistics and connectivity infrastructure etc. Jobs creation remains crucial and focus should be on deepening and widening the labour market. A BI could remain as a safety net, but not as an alternative to employment generation.

For now, a targeted income support should be the priority rather than universal one because poorer households require more help than richer ones. Income support would boost demand as well as provide a safety net.The situation surely justifies temporary emergency income payments rather than a permanent income stream. The recent UNDP report concludes that the measure is feasible and urgently needed. A guaranteed basic income system can be a source of basic security for the poor. It should be paid at least for the duration of the pandemic and economic slowdown.

Raghuram Rajan has also advocated a temporary income transfer scheme. But Jean Dreze is skeptical that an emergency BI scheme can be quickly implemented. He voices concern if income transfers are meant to replace programmes like PDS and MGNREGS.

Rapid and inclusive economic growth is the most powerful poverty-reduction tool in the long term. In the interim, the core complementarity between income and in-kind transfers should be understood. A mix of cash as well as in-kind transfers like food is vital for an efficient response to the crisis.

Spread the Word