THE CONTEXT: Recently, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) has arrested a top official of the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO), the regulatory body for drug approvals in India, and a senior official in charge of regulatory affairs of a Bengaluru-based pharmaceutical firm as well as officials of a company acting as middlemen on behalf of the pharma company. This development again raised questions on the flaws in the drug regulation in India and highlighted the need for a strong mechanism for drug and pharmaceutical regulations. Daily analysis for the issue is as follows.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF REGULATION

The regulatory scenario in this sector is extremely crucial not only due to the rapid and ongoing changes at the global level, largely with reference to good manufacturing practices (GMP), good clinical practices (GCP)and good laboratory practices (GLP) but also due to the onus on the regulatory bodies to ensure a healthy supply of quality drugs at affordable prices to the Indian masses.

WHY THERE IS A NEED FOR REGULATION?

REASON

DETAILS

INFLATED FEES BY PRIVATE HOSPITALS

- The Drug Price Control Order of 2013 stipulates a ceiling of MRP for medicines mainly in the national list of essential medicines and has provided full freedom to the pharmaceutical companies to fix the MRP at a high level.

- This provides the regulatory space to facilitate corporate hospitals to demand high mark-ups from pharmaceutical companies.

- The NPPA analyses show that a major portion of hospital bills – 55% – is payments for medicines and other consumables.

Case study:

- In 2017, the country was shocked to hear that two families had to pay nearly Rs 16 lakhs each for the two weeks of inpatient care of their children for the treatment of dengue-related complications.

- The National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA) inquiry into these two inflated charges revealed that hospitals were producing medicines at a cheap price and selling them to patients at the maximum retail price (MRP).

- An analysis, by the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA), of Fortis Hospital’s bill of medicines and consumables of one such patient, shows the exorbitant charges: an IV Infusion set procured for Rs. 8.39 is sold to the patient for Rs. 115, a margin of 1,271 per cent. Similarly, a disposable syringe procured for Rs. 15.90 was sold to the patient for Rs. 205, a margin of 1,189 per cent.

- The analyses of the hospital bills found a mark up between 375% and 1700%.

FAILED PAST ATTEMPTS DUE TO REGULATORY LOOPHOLE

- Past experiences show that even if the government caps the margins or prices of the consumables, the hospitals then increase the charges for procedures and other services and refuse to pass on the benefit to the patients.

- Example: In the case of cardiovascular stents, immediately after the prices were capped, hospitals increased the charges for procedures.

- Therefore any effective remedy to ensure affordable healthcare charges can be done only through the ceiling of healthcare charges in private hospitals.

SHRUGGING OFF THE RESPONSIBILITY BY THE CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

- With health being a State subject, the Central government says it cannot step in to regulate healthcare charges.

- The Central Clinical Establishment Rules, which is to implement the Central Clinical Establishment Act (CEA) stipulates that the clinical establishments shall charge the rates for procedures and services fixed by the Central government in consultation with the state government.

- Though the rules were framed in 2012, the Central government has not fixed the rates.

- Draft Charter of Patients Rights, a joint initiative of the National Human Rights Commission and Ministers of Health is also silent on the ceiling of health charges.

- The Charter, without any regulation or ceiling on healthcare charges, would not offer any relief to the people who are exposed to financial exploitation from private sector hospitals.

INTERNATIONAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL OBLIGATIONS

- India, as a party to the International Covenant on Social and Economic Cultural Rights, has an international obligation to protect its population from the exploitation of private hospitals.

- Similarly, the right to health is recognised as a fundamental right under Article 21 of the constitution which places a constitutional obligation upon both the Union and state governments to regulate healthcare charges.

NO CLEAR DEFINITION/REGULATION FOR GENERIC AND SPURIOUS DRUG

- There is no definition of generic or branded medicines under the Drugs & Cosmetics Act, 1940 and Rules, 1945 made thereunder.

- However, Clause 1.5 of Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) Regulations, 2002 prescribes that every physician should prescribe drugs with generic names legibly and preferably in capital letters and he/she shall ensure that there is a rational prescription and use of drug.

- But, the regulation related to both medicine is not implemented so far. There is a clear vacuum related to their in terms of regulation and difference of both these drug.

PROMOTION OF DOLO DURING RECENT PANDEMIC

- In the absence of clear guidelines and regulation, DOLO non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (a harmful pain killer) promoted at wide level.

- This shows that why there is need for an effective regulations for such of harmful medicine.

MAJOR BODIES REGULATING DRUGS AND PHARMACEUTICALS

MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE

Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)

Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO) headed by the Drug Controller General of India, DCGI (I) + Statutory Committees + Advisory Committees +

State Licensing Authorities

MINISTRY OF CHEMICALS AND FERTILIZERS

Department of Pharmaceuticals

National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA): Drugs (Prices Control) Order (DPCO) 2013

MINISTRY OF COMMERCE

Patent Office

Controller General of Patent

MINISTRY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

Department of Biotechnology (DBT)

Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) Laboratories

MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT

Environmental clearance for manufacturing

ROLE OF DIFFERENT DRUG REGULATING AGENCIES

The Central Drug Standards and Control Organization (CDSCO)

(Ministry of Health and Family Welfare)

Prescribes standards and measures for ensuring the safety,

Efficacy and quality of drugs, cosmetics, diagnostics and devices in the country;

Regulates the market authorization of new drugs and clinical trials standards;

Supervises drug imports and approves licences to manufacture the above-mentioned products.

The National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA),

( Department of Chemicals and Petrochemicals)

Fixes or revises the prices of decontrolled bulk drugs and formulations at judicious intervals;

Periodically updates the list under price control through inclusion and exclusion of drugs in accordance with established guidelines;

Maintains data on production, exports and imports and market share of pharmaceutical firms;

Enforces and monitors the availability of medicines in addition to imparting inputs to parliament on issues pertaining to drug pricing.

STATE DRUG REGULATING AUTHORITY(SDRA)

Licenses and monitoring manufacture,

Distribution and sale of drugs and other related products.

THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR PHARMA SECTOR

In India, drug manufacturing, quality and marketing are regulated in accordance with

- Drugs and Cosmetics Act of 1940 and Rules 1945

- Pharmacy Act of 1948

- Drugs and Magic Remedies Act of 1954

- Drug Prices Control Order (DPCO) 1995, 2013

In accordance with the Act of 1940, there exists a system of dual regulatory control or control at both Central and State government levels

INSTITUTIONAL ISSUES RELATED TO REGULATING BODIES IN PHARMA SECTOR

(ADMINISTRATION)

REGULATING BODIES

ISSUES

THE NATIONAL PHARMACEUTICAL PRICING AUTHORITY

- NPPA chairman is an officer of the secretary level from Indian administrative services.

- There is no fixed tenure of chairmen. Further, there are no permanent staff at NPPA.

- For implementing its order, NPPA has to depend upon state authorities.

- NPPA can only control the price of drugs which are under NLEM (which is in stark contrast with its motto “affordable medicine for all”) previously, it can control prices of other drugs also using Para 19 of DPCO order, but it has since been deleted.

THE CENTRAL DRUG STANDARDS AND CONTROL ORGANIZATION (CDSCO)

Lack of access to resources (both physical infrastructure and human resources)

THE DRUGS CONTROLLER GENERAL OF INDIA (DCGI)

MDs in pharmacology and/or microbiology are given preference for appointment to the job of the Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI): this can generate a conflict of interest sometimes.

STATE DRUG REGULATORY AUTHORITY(SDRA)

- Most of the regulators are pharmacists: this creates a conflict as; most of the regulators at the central level are Doctors.

- Lack of access to resources (both physical infrastructure and human resources)

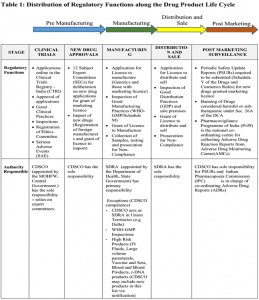

From the table below it will be clear that both the CDSCO and the SDRAs exercise regulatory control exclusively on the basis of executive fiat and delegation. In effect, both have limited Pre Manufacturing Distribution and Sale Post Marketing operational freedom and, therefore flexibility, to develop and operationalise their regulatory powers.

CHALLENGES IN PHARMA REGULATION SECTOR (FUNCTIONING)

AUTONOMY

- Both the CDSCO and the SDRAs are umbilically tied to their parent ministries and departments of health respectively. This impedes flexibility in decision-making and autonomy in a host of areas beginning with finance, recruitment and other areas of institutional policy. Regulators are effectively accountable to bureaucrats in their respective parent ministries.

- Any decision passes through various ministerial channels,weakening the autonomy of CDSCO.

- The CDSCO is not a statutory body and, therefore, is not independent of the MOHFW. The CDSCO is headed by the Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI). A similar structure operates at the state level where the State Drug Controller (SDC) heads the SDRA and reports to a joint secretary in the health department of state government AND HENCE OVERLAPPING JURISDICTIONS.

- Fees collected by the CDSCO are routed through the Department of Health, thus budgetary allocation is the only source of finance

- Fragmented drug regulators further decrease their autonomy as the power to regulate the Drug industry is at different levels VIZ. CDSCO,NPAA,SDRA

- Lack of hierarchy between CDSCO and the SDRAs as both are legally entitled to function autonomously since ‘health’ is a subject; this creates a continuous challenge in ensuring harmonised application of drug regulatory standards throughout the country.

POWER

- Section 33P15 which empowers the CDSCO to issue directions to SDRAs, to ensure that provisions of DCA are implemented uniformly in all states, has been rarely used and, even if it is used, the CDSCO has no power to enforce compliance by states.

- Drug inspectors have no assurance of their safety and do not have the power to arrest

- power of SDRA to inspect the drug only at the market level (off the sleeve whereas in most of the countries it is done at the process level)

- lack of power to punish the doctors who give verbatim because of pharmaceutical lobbying on clinical trials of drugs

CAPACITY

- AT THE ADMINISTRATIVE LEVEL, Lack of access to resources (both physical infrastructure and human resources.

- AT THE FINANCIAL LEVEL, BOTH ORGANISATION COMPLETELY DEPENDS UPON BUDGETARY ALLOCATION, and a minimal user fee is charged FROM THE INDUSTRY

- lack of planning and execution of training programmes for drug inspectors/ad hoc in approach

- institutional channels of interaction between the CDSCO and the SDRAs are lacking.

1. Method to calculate ceiling prices

- DPCO, 2013 lays down a complicated formula: “(Sum of prices to the retailer of all the brands and generic versions of the medicine having market share more than or equal to one per cent of the total market turnover on the basis of moving annual turnover of that medicine) / (Total number of such brands and generic versions of the medicine having market share more than or equal to one per cent of total market turnover on the basis of moving annual turnover for that medicine.)”

- In other words, the ceiling price is the average of price of all brands of medicine with more than 1% market share.

WHAT ARE THE SHORTCOMINGS IN THE PRESENT SYSTEM OF CONTROL IN INDIA?

HEALTH INSURANCE SCHEMES ARE NOT EFFECTIVE

- Instead of directly intervening and regulating the healthcare charges, the state and Central governments intervened through insurance schemes to reduce the financial burden of patients.

- These schemes function as a cross-subsidization or by increasing footfalls for the private sector.

- Studies have shown that even after insurance schemes like the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) and various state government-sponsored insurance schemes; there is no change in the burden of out-of-pocket expenditure.

- Often hospitals use these schemes to attract patients and charge them heavily by offering services outside the scheme.

REGULATORY CAPTURE

- Regulatory capture is a phenomenon when a regulatory body gets influenced by the economic interests of special interest groups that dominate the industry, rather than those of the general public.

- A regulatory capture is a form of government failure, where government agencies fail to perform their duties.

WEAK IMPLEMENTATION BY THE GOVERNMENT

- Loopholes in policy design are complicated by weaknesses in implementation.

- The government leaking out information on the dosage of a drug whose price is under regulation is an example of a loophole in policy design.

- Also,

NO DETERRENCE OF PUNITIVE ACTIONS

- There are no punishment methods if a firm fails to adhere to the price cap or is strategically launching a new variant of the drug to bypass regulation.

- Violation of the price-cap ceiling imposed by DPCO 2013 has not attracted any punitive consequences for firms.

NO EFFECTIVE MONITORING MECHANISM

- Neither the Department of Pharmaceuticals nor the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority has the institutional ability to monitor the prices of medicines at the state level. Such capacities are key to the enforcement of the regulation.

OVERVIEW OF MAJOR REFORM EFFORTS

ON AUTONOMY

RANJIT ROY CHAUDHARY COMMITTEE REPORT

CDSCO should be upgraded to a separate organisation with functional and financial autonomy. DCGI qualification and experience should be similar to that of a secretary or director general.

MASHELKAR COMMITTEE REPORT

Independent CENTRAL DRUG AUTHORITY reporting directly to the Ministry of Health.

Financing

59th Report on the Functioning of CDSCO

MOHFW should work out a fully centrally sponsored scheme for the purpose so that the state drug regulatory authorities do not continue to suffer from a lack of infrastructure and manpower anymore.

Mashelkar Committee Report

Requires more budgetary allocation for setting up world-class drug controlling authority

MANPOWER

Ranjit Roy Chaudhary Committee

Identification and creation of positions in different disciplines have become more important in drug regulation. this can be solved by better emoluments

Mashelkar Committee

creation of new posts

Augment no. of drug inspectors

The capabilities and skills of enforcement staff need to be upgraded

59th Report on the Functioning of CDSCO

Engagement of medically and professionally qualified persons on a short-term contract or on deputation basis of interest agreements.

Infrastructure

Ranjit Roy Chaudhary Committee

Expand the current pharmacovigilance programme to cover the whole country by strengthening Zonal and sub zonal office

Mashelkar Committee

The state must provide adequate infrastructure for the office of DRA, including vehicles and the purchase of samples.

59th Report on the Functioning of CDSCO

Upgrade existing offices and set up new offices

Strengthen both central and state drug testing laboratories

THE WAY FORWARD:

QUALITY + AFFORDABILITY

Ø The system of healthcare in India should be balanced between quality healthcare and affordability.

Ø To achieve this, both policymakers and firms need to meet somewhere mid-way to find a win-win solution.

ROLE OF CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

Ø The Central government, which has the experience of capping the price of healthcare services under the CGHS scheme, should use its powers under the Concurrent List to stop the burden-shifting and establish a regulatory authority to fix ceiling prices on healthcare services.

Ø Even though health is listed as a state subject, the constitution provides the Union government with enough powers to regulate healthcare fees.

Ø Article 243 of the constitution provides legislative competence to the Union government to legislate upon any subject matter in the state list to fulfil an international obligation.

Ø The concurrent list entries, like price control and essential services, provide powers to the Central government to regulate the healthcare charges of private hospitals.

REFORMS IN THE DRUG DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM

Ø The drug distribution system could be reformed in India, by building up the scale and scope of generic medicine pharmacies as in the Jan Aushadhi Programme, a campaign launched by the Government of India to provide quality generic medicines at affordable prices to the masses.

SUPPLY-SIDE REFORMS

Ø The industry’s reputation from the supply side can be improved by responsible pricing behaviour and complementary programs to enhance the diffusion of their medicines and healthcare products to the less privileged at highly subsidised prices.

THE CONCLUSION: At the helm, we need persons of vision with an understanding of the importance of evidence-based medicine in public health and curative healthcare, as well as an understanding of the general progress of the science of medicine, pharmacology and pharmaceutics – these may be found in a wide range of associated disciplines, for mitigating the case of conflict of interest. National pharmaceutical policy is an opportunity to radically clean the anarchy in drug regulation in India in the interests of public health. Surely, “The Pharmacy of the World” deserves a better regulatory body.

MAINS QUESTIONS

- Discuss the regulatory loopholes in the healthcare system in India, especially related to drug price control.

- With healthcare being a State subject, the Centre has less power and responsibility in ensuring the right to health for everyone. Do you agree with the statement? Give reasons to justify your viewpoint.

- Discuss the strategies that can be applied to make healthcare in India affordable to each and every one.