Table of Contents

THE CONTEXT: India’s record in promoting occupational and industrial safety remains weak even with years of robust economic growth. Making work environments safer is a low priority, although the productivity benefits of such investments have always been clear. Although occupational safety and health (OSH) is an existential human and labour right, it has not received due attention from lawmakers and even trades unions in India. This article analyses the issue of occupational safety and health in detail.

THE ILO DECLARATION ON FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES AND RIGHTS AT WORK

The ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (FPRW) , adopted in 1998 and amended in 2022, is an expression of commitment by governments, employers and workers’ organizations to uphold basic human values – values that are vital to our social and economic lives. It affirms the obligations and commitments that are inherent in membership of the ILO, namely:

- freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining;

- the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour;

- the effective abolition of child labour;

- the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation; and

- a safe and healthy working environment. (added in 2022)

THE INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION’S FUNDAMENTAL CONVENTIONS

Embedded in the ILO Constitution, the principles and rights mentioned above have been expressed and developed in the form of specific rights and obligations in Conventions recognized as fundamental both within and outside the Organization. These ILO Conventions have been identified as fundamental, and are at times referred to as the core labour standards:

- Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No. 87)

- Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention,1949 (No. 98)

- Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29)

- Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957 (No. 105)

- Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (No. 138)

- Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182)

- Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951 (No. 100)

- Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111)

The ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work applies to all States belonging to the ILO, whether or not they have ratified the core Conventions.

WHY SOME COUNTRIES HAVE NOT RATIFIED THE CONVENTIONS:

- Even though the FPRW was a valiant statement of reaffirming a set of labour rights as core and undeniable human rights, there existed cracks within the FPRW for reasons such as:

- With the identification of a handful of conventions as core conventions, ILO has created a hierarchy of its own labour standards.

- It also implicitly under-valued the informal economy as freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining in a large sense relate to the small formal economy in the vast majority of poor and developing countries.

- Countries differ in terms of their stages in economic development and standards, OSH and minimum wages could not be brought under the FPRW framework, for they would have differential, if not difficult, economic outcomes for less developed and poor countries.

- There is no disagreement among any country that forced labour is not permissible. Though with respect to the elimination of child labour, poor countries justified the same on grounds of economic poverty.

INCLUDING OSH AS A CORE LABOUR RIGHT

FOR

- Some 2.3 million people die each year due to workplace illness and accidents and the current pandemic will only add to this appalling loss of human life. Many millions more have been injured or have long-term illnesses from their work. The right to protection from deadly work processes, noxious chemicals and other hazards must be recognised as a fundamental right, along with freedom of association and collective bargaining and protection from discrimination, forced labour and child labour.

- Several global OSH bodies like The Institution of Occupational Safety and Health strongly backed the International Trade Union Council’s (‘ITUC’) call for the inclusion of OSH as a part of fundamental rights.

AGAINST

- The International Organization of Employers recognized the value of OSH, it did not want to elevate it to a fundamental right alongside FOA and CB. It argued that OSH is frequently the result of irresponsible behaviour of workers and that OSH could be addressed in ways other than making a fundamental right.

Ø On 23 March 2022, the ILO’s Governing Body, a tripartite committee overwhelmingly supported a call from worker members to move ahead with the process to designate occupational health and safety an ILO Fundamental Right at Work (FRAW).

Ø In the plenary session of the ILC held on 10 June 2022, the delegates adopted a resolution to add the principle of “a safe and healthy working environment” to the ILO’s FPRW 1998.

Ø Two ILO Conventions concerning OSH have been added to the ILO’s Core Conventions, viz. Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No. 155) , and the Promotional Framework for Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 2006 (No. 187).

C.155

- C.155 applies to all branches of economic activity in which workers, that is, all employed persons including public employees, are employed, including public services, and to all workers therein. The term “workplace” covers all places where workers need to be at or to go by reason of their work, and which are under the direct or indirect control of the employer.

- All member countries in consonance with the conditions prevalent in them formulate, implement and review periodically a national policy on OSH. The aim of the policy “shall be to prevent accidents and injury to health arising out of, linked with or occurring in the course of work, by minimising, so far as is reasonably practicable, the causes of hazards inherent in the working environment.”

C.187

- According to C.187, there must be in place a national policy and a national system for occupational safety and health, a national programme on occupational safety and health, and national preventative safety and health culture.

THE KEY INSTRUMENTS OF OSH:

ILO notes that more than 40 standards deal specifically with OSH and “nearly half of ILO instruments” deal directly or indirectly with OSH issues. These key instruments are divided into three aspects:

ASPECTS

KEY INSTRUMENTS

ON OSH

- Promotional Framework for OSH Convention, 2006 (C.187),

- OSH Convention, 1981 (C.155), and

- Occupational Health services Convention, 1985 (C.161);

ON HEALTH AND SAFETY IN PARTICULAR BRANCHES OF ECONOMIC ACTIVITY

- Hygiene (Commerce and Offices) Convention, 1964 (C.120),

- Occupational Safety and Health (Dock Work) Convention, 1979 (C.152),

- Safety and Health in Construction Convention, 1988 (C.167),

- Safety and Health in Mines Convention, 1995 (C.176), and

- Safety and Health in Agriculture Convention, 2001 (C.184);

ON PROTECTION AGAINST SPECIFIC RISKS

- Radiation Protection Convention, 1960, (C.115),

- Occupational Cancer Convention, 1974 (C.139),

- Working Environment (Air Pollution, Noise and Vibration) Convention), 1977 (C.148),

- Asbestos Convention, 1986 (C.162), and

- Chemicals Convention, 1990 (C.170).

To date, India has ratified only 47 Conventions and one Protocol. India has ratified several conventions which are somehow related to OSH, that is, hours of work, accidents, occupational diseases, and so on.

However, it has ratified only one of the Conventions noted above, which is, C.115 – Radiation Protection Convention, 1960 (No. 115) in 1975.

INDIA AND OSH:

- In India, we have labour laws covering certain primary economic activities like factories, ports and docks, mines, plantations, and construction, among others. There exist elaborate measures to ensure workers’ safety and health in them.

- The newly framed Code on Occupational Safety and Health and Working Conditions, 2020 has also put together the laws for various sectors like factories, mines, plantations, construction, and so on, however, some shortcomings and lacunas still exist. While the Code introduces some new provisions relating to OSH, it dilutes the existing ones. For instance:

- Earlier, under the Factories Act, 1948, every factory carrying out hazardous processes or a hazardous factory had to have in place a bi-partite Safety Committee. Now, the constitution of the Safety Committee has been left to the executive process of “government notification”. Further, Safety Officers are required to be appointed only in factories or mines or plantations employing a certain number of workers. Both of these clauses seriously dilute OSH.

- The Directorate General, Factory Advice Service and Labour Institutes (‘DGFASLI’) deal with the safety and health of workers employed in factories and ports. The Director General of Mines and Safety is concerned with the safety and health of mining workers. There is no agency nor any other labour law to cover the workers in unorganized workers, and those working in the micro, small and medium establishments.

- There is no direct law to regulate OSH in agriculture as there are in other branches of economic activity.

- The statistical system that exists in India provides unreliable and often incomplete statistics on industrial relations relating to industrial accidents. The statistical system conceived during the early years of the planned economy continues even now. For instance:

- The Indian Labour Statistics (an annual flagship publication of the Labour Bureau) publishes data on industrial accidents relating to four sectors: factories, mines, ports, and railways. Over so many decades, no more sectors have been added. The construction Sector is one such glaring omission.

OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH PROBLEMS IN THE INFORMAL SECTOR

- The informal sector or unorganized sector includes all those workers and tiny economic units that are not recognized, recorded, protected or regulated by formal arrangements in law or in practice. Unorganized workers do not have the social security benefits that workers in the formal sector enjoy from their employers and government. These workers are often exposed to various occupational hazards during their course of employment. Due to a lack of regulations governing occupational safety and standards in the unorganized sector, the occurrence of occupational diseases is common among these workers.

- The most common examples of informal employment in India are agriculture, construction work, carpet weaving, beedi making, garment making, blacksmith and welding, pottery, agarbatti making, food vending, domestic employment, auto and rickshaw driving, local car and two wheeler workshops, rag picking and manual scavenging. All these employments are associated with exposure to hazards and risks to various occupational diseases.

- Workers in informal sectors are not using protective devices and that aggravate risk to respiratory illnesses, eye problems, skin problem, hearing loss etc. The temporary nature of the occupational setup and belonging to poor socioeconomic status reduces their priority to occupational health and safety.

- No reliable government data on the numbers of the person involved in the informal sector, their working conditions and specific health hazards leads to difficulty in making policy and doing interventions on a large scale.

- Worksites and institutions should be encouraged and monitored to ensure safe health practices and accident prevention, besides providing preventive and promotive health care services. This can be started by formulating national health care guidelines for informal sector workers. Methods to implement these guidelines should also be discussed in detail.

THE ROLE OF CIVIL SOCIETY IN SECURING WORKERS’ RIGHTS, OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY PROVISIONS

- Civil society is the “sum total of all individual and collective initiatives for the public good”. The role of civil society and CSOs comprises a wide-ranging plethora of diverse activities. Associations of civil society that pursue a common purpose/deliver a public good include Traditional Associations, Religious Associations, Social Movements, Membership based (representational, professional, socio-cultural, self-help) and Intermediary Organisations (service delivery, mobilizing, support, philanthropic, advocacy, network).

- Various types of organizations engage at various levels. The nature of CSO activities can range from policy influencing to achieving certain goals (including evidence and agenda setting, policy development, advocacy, mobilization, consensus building, policy and accountability monitoring/watchdog work), to direct service provision (such as education, health, etc), to technical standard-setting, self-regulation through the creation and enforcement of best practices, and partnerships with the government to enhance their capacity to deliver essential services.

- This holds true for CSOs working on Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) and labour rights with the goal of securing workers’ rights to compensation. Often, these efforts take place within larger movements to secure health for all persons nationally. All CSOs have a different guiding ethos driving their efforts and espouse different theories of change to effect those changes in the long term.

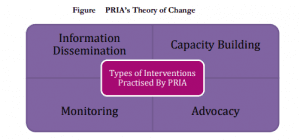

- For instance, PRIA’s theory of change, involving efforts at the micro, meso and macro levels, as a CSO is depicted in the Figure given below. PRIA’s efforts are grounded in its ethos of participatory research, action and development. Enabling the excluded and the marginalised to gain and then exercise their agency, and informing, capacitating and empowering communities to incorporate their knowledge into solutions for themselves forms the bedrock of PRIA’s efforts. [Established in 1982, PRIA (Participatory Research in Asia) is a global centre for participatory research and training based in New Delhi. PRIA has linkages with 3000 NGOs to deliver its programmes on the ground.]

- Information Dissemination: One of the most crucial aspects of ensuring workers’ health and safety is building awareness about occupational hazards and existing provisions enabling workers’ rights. PRIA has carried this out by spreading information about the occupational hazards of silicosis among not just workers, but also medical professionals, local and national government officials, and communities at large. Seminars and campaigns were organised to help increase knowledge and awareness about the disease and how it could be dealt with at the workplace.

- Capacity Building: Knowledge and information dissemination is also an essential part of the overall capacity building that PRIA undertook with workers. Workers were made aware of information and strategies they could use to secure their rights. This included building the skills they needed and the awareness of the need to unionise and demand better working conditions at their workplaces.

- Monitoring: PRIA monitored and evaluated the implementation of specific projects, programs and policies to see how effective they were in actually effecting a change in the conditions of the workers.

- Advocacy: PRIA also engaged in various advocacy initiatives to influence policies and changes that were made in the working conditions of the individuals suffering from silicosis, and to ensure proper diagnosis and treatment. Workers’ rights are also actively championed through activism on the ground and now increasingly on social media. Several organisations are engaged in this, along with awareness raising.

DOMESTIC WORKER AND LABOUR LAWS

- Domestic workers are those workers who perform work in or for a private household or households. They provide direct and indirect care services, and as such are key members of the care economy. Their work may include tasks such as cleaning the house, cooking, washing and ironing clothes, taking care of children, or elderly or sick members of a family, gardening, guarding the house, driving for the family, and even taking care of household pets.

- Of the 75.6 million domestic workers worldwide, 76.2 per cent are women, meaning that a quarter of domestic workers are men. Domestic work is a more important source of employment though among female employees than among male employees.

- Although they provide essential services, domestic workers rarely have access to rights and protection. Around 81 per cent are in informal employment – that’s twice the share of informal employment among other employees. They also face some of the most strenuous working conditions. They earn 56 per cent of the average monthly wages of other employees and are more likely than other workers to work either very long or very short hours, they are also vulnerable to violence and harassment, and restrictions on freedom of movement. Informal domestic workers are particularly vulnerable. Informality in domestic work can partly be attributed to gaps in national labour and social security legislation, and partly to gaps in implementation.

REPORT PUBLISHED BY THE COMMONWEALTH HUMAN RIGHTS INITIATIVE (CHRI):

- While domestic workers across the world have suffered in the COVID-19 pandemic, the astounding lack of overarching legal or policy provisions in India to safeguard their wellbeing has meant a dire downward spiral for men and women in this sector in the last year, a report has found. The report published by the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) notes that while the pandemic has demonstrated how integral domestic care and assistance is, this has not translated into an alleviation of the situation of domestic workers.

- But more importantly, governments do not appear keen to resolve this either. Only six out of 54 Commonwealth countries have ratified the Domestic Workers Convention (C189) – 10 years after it was brought to ensure decent conditions for domestic workers. India is not one of the six.

- The report calls for bold laws to eradicate the worst forms of child labour and adds that it would be in line with what India, as a signatory to the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Target 8.7 and the ILO Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999, has claimed to aim for. However, the e-Shram portal which aims to register 38 crore unorganised workers in the country and the formulation of the Labour Codes as steps taken by the Union government towards ensuring safeguards for unorganised, including domestic, laborers is worth the praise.

- The report further recognises that a huge chunk of the work to ensure domestic workers get benefits are done by unions across the country and calls for civil society to encourage unionisation and collective action among domestic workers, including referrals to the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) and/or the National Domestic Workers Movement (NDWM) as appropriate.

- All such factors as mentioned in the report contributes to the call for India to ratify the C189, as a step towards streamlining national protections for domestic workers.

GIG WORKERS AND LABOUR LAWS IN INDIA

In an attempt to incorporate the doctrine of universalisation of social security, the gig workers are brought into the ambit of the labour laws for the first time, with the provision of some welfare measures under the Code on Social Security, 2020. The three other codes are silent on the policies toward gig workers.

In addition to the inclusion of laws for gig workers in the Code on Social Security, the Code on Industrial Relations, 2020 could have dealt with defining the nature of the relationship and the contract between the gig workers and the platforms by widening the scope of the ambit of employment relationships. When gig workers in many platforms are incentivised to work heavily ignoring the long-term health impacts, fixing maximum working hours and workplace safety measures could be covered in the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code.

OCCUPATIONAL HAZARDS IN INDIA

PNEUMOCONIOSIS:

- Pneumoconiosis is the general term for a class of interstitial lung diseases (the tissue and space around the alveoli) where inhalation of dust has caused interstitial fibrosis.

- It is an occupational health disease and mostly affects workers who work in the mining and construction sectors.

- Depending upon the type of dust, the disease is given different names:

- Coal worker’s pneumoconiosis (also known as miner’s lung, black lung or anthracosis) — coal, carbon

- Asbestosis — asbestos

- Silicosis (also known as “grinder’s disease”) – silica dust.

ABOUT SILICOSIS:

- Silicosis can be described as an occupational disease or hazard due to dust exposure. It is incurable and can cause permanent disability. However, it is totally preventable by available control measures and technology.

- Silica (SiO2/silicon dioxide) is a crystal-like mineral found in abundance in sand, rock, and quartz. It is a progressive lung disease caused by the inhalation of silica over a long period of time, characterized by shortness of breath, cough, fever and bluish skin.

- In India silicosis is prevalent in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Pondicherry, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Orissa and West Bengal among the workers of construction and mining.

LEGAL PROVISIONS:

- Silicosis is a notified disease under the Mines Act (1952) and the Factories Act (1948) which mandates a well-ventilated working environment, provisions for protection from dust, reduction of overcrowding and provision of basic occupational health care.

- Self-Registration: A system of worker self-registration, diagnosis through district-level pneumoconiosis boards and compensation from the District Mineral Foundation Trust (DMFT) funds to which mine owners contribute.

- Occupational Safety, Health, and Working Condition Code 2020 (OSHWC): The code makes it mandatory for all employers to provide annual health checks free of cost as prescribed by the appropriate Government.

THE ANALYSIS:

Two of the largest employing sectors in India, namely agriculture and the micro, small and medium sectors, are not regulated by any law.The agriculture sector is lacking on legislation on safety and health for the workers working in this sector. There are certain Acts on occupational safety and health pertaining to certain equipments or substances, such as, the Dangerous Machines Regulation Act, the Insecticides Act. The enforcement authorities are not identified under these Acts and hence are not being enforced. The agriculture sector is the largest sector of economic activity and needs to be regulated for safety and health aspects. Lack of legislation on safety and health in the agriculture sector is also hindering the ratification of ILO convention 155. Industries under MSME also do not have any legislation to cover the safety and health of the workers which makes it difficult for India to ratify C.187.

However it must be understood that a safe and healthy workplace prevents accidents and occupational diseases; reduces, if not prevents, industrial accidents, especially fatal ones, thus ensuring higher participation of workers in economic activity, improves productivity, and thereby, in an overall sense, boosts economic efficiency, which eventually means higher economic growth. And hence employers must see the expenses on OSH, not as a liability but an investment.

THE WAY FORWARD:

- India should establish efficient Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) data collection systems to better understand the situation for effective interventions. The labour codes, especially the OSH Code, the inspection and the labour statistical systems need to be reviewed and be made more effective as the Government is in the process of framing the Vision@2047 document.

- Article 39(e) of the Constitution directs the State to ensure “that the health and strength of workers, men and women, and the tender age of children are not abused and that citizens are not forced by economic necessity to enter avocations unsuited to their age or strength;” further, as per Article 42, the State “shall make provision for securing just and humane conditions of work and for maternity relief.” The state shall take proactive steps in realising such principles envisaged by the makers of our constitution which becomes even more imperative in the aftermath of the Covid pandemic.

- The Government of India in 2019 declared the National Policy on Safety, Health and Environment at Workplace (NPSHEW) which aims to establish a preventive safety and health culture in the country through the elimination of the incidence of work-related injuries, diseases, fatalities, disasters and to enhance the well-being of employees in all the sectors of economic activity in the country. The policy recognizes the role of OSH’s contribution toward productivity, growth and overall welfare of people. It also identifies the role of some factors like changing job patterns and sub-contracting in posing problems in managing OSH; the role of technology in mitigating hazards, but also new risks arising out of it. The Policy, in short, makes the right signals, including stressing the need for an adequate and effective labour inspection system which must be acted upon proactively, will also help India in the direction towards ratifying the C.155.

- India faces large challenges in its efforts toward ratification of conventions relating to OSH. A progressive step that it could take in this direction is to endorse the FPRW which includes “a safe and healthy working environment” as another fundamental principle. Trade unions, academics, and more importantly, industry bodies must lobby the government toward these measures.

THE CONCLUSION: The labour agenda is never finished. The walk is long and strenuous as neoliberal globalization is more likely to put obstacles to the realization of rights as fundamental principles. It would indeed be a challenge as the world of work is undergoing profound changes. It is important for governments, employers and workers, and other stakeholders to seize the opportunities to create a safe and healthy future workplace for all. Their day-to-day efforts to improve safety and health at work can directly contribute to the sound socio-economic development of India.

Mains Practice Questions:

- Even after having the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code 2020, India has not ratified the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. What is hindering India in ratifying the convention and what should India do to further enhance the safety and health of workers?

- ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (FPRW) was amended in 2022 to include “a safe and healthy working environment” as a basic human value. Comment.