THE CONTEXT: The government’s macro-economic strategy, as articulated through the Budget and the Economic Survey, can be stated simply: Growth will take care of all problems, as it had worked for India previously. Yet many parameters have changed since then.

THE ISSUE: After the LPG era when the macro-economic indicators were comparable to today’s fiscal deficits, heavy interest burden on public debt, and problem-ridden banks. Yet the silver lining was world economy was growing which boosted tax revenues, reduced the deficit and debt in relation to GDP, and helped digest the interest burden. However, that scenario has changed since. In such a case, what’s the viability of growth being the centerpiece for the development in India?

THE SHACKLES NOW: Due to inflationary pressure now, low-interest rates are climbing. While the global economy was accelerating then, it is slowing now. So, if the government thinks growth is the solution, can it be delivered in a slowing world with rising rates — bearing in mind also the domestic context of slower growth even during the pre-pandemic phase?

THE QUESTION NOW: In this case, given the status of the economy now Indian growth rate can sustain for 2-3 years, after which it will come under various traps. Some of these traps are

TRAPPED INDIA

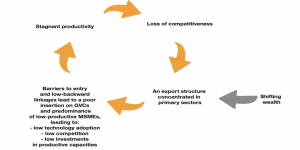

Productivity trap: Persistently low productivity levels and poor productivity, performance across sectors in India are symptoms of a productivity trap. The concentration of exports of India on primary and extractive sectors undermines the participation of India in global value chains (GVCs). This, in turn, is associated with low levels of technology adoption and few incentives to invest in productive capacities. In all, competitiveness remains low, making it difficult to move towards higher added-value segments of GVCs. This fuels a vicious circle that negatively affects productivity.

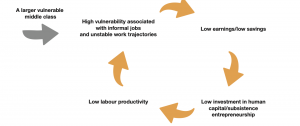

Social vulnerability trap: Income growth paired with strong social policies since the beginning of the century has reduced poverty remarkably. Yet most of those who escaped poverty are now part of a new vulnerable middle class that represents 40% of the population. This comes with new challenges, as more people are now affected by a social vulnerability trap that perpetuates their vulnerable status. Those belonging to this socio-economic group have low quality, usually informal jobs associated with low social protection and low – and often unstable – income. Because of these circumstances, they do not invest in their human capital or lack the capacity to save and invest in entrepreneurial activity. Under these conditions, they remain with low levels of productivity, hence only with access to low-quality and unstable jobs that leave them vulnerable. This trap operates at the level of the individual, who is locked into a vulnerable status; this contrasts with the productivity trap, which refers to the whole economy.

Institutional trap: The expansion of the middle class in India has been accompanied by new expectations and aspirations for better quality public services and institutions. However, institutions have not been able to respond effectively to these increasing demands. This has created an institutional trap, as declining trust and satisfaction levels are deepening social disengagement. Citizens are seeing less value in committing to the fulfillment of their social obligations, such as paying taxes. Tax revenues are thus negatively affected, limiting available resources for public institutions to provide better quality goods and services, and to respond to the rising aspirations of society. This creates a vicious circle that jeopardizes the social contract in the region.

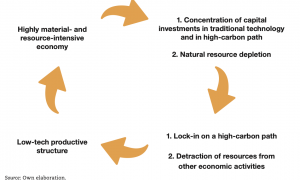

Environmental trap: This is linked to the productive structure of most developing economies, which is biased towards high material and natural resource-intensive activities. This concentration may be leading these countries towards an environmentally and economically unsustainable dynamic for two reasons. A concentration on a high-carbon growth path is difficult – and costly – to abandon; and natural resources upon which the model is based are depleting, making it unsustainable. This has also gained importance in recent years, with the stronger commitment to global efforts to fight climate change.

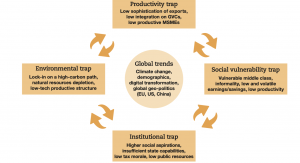

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN THESE DEVELOPMENT TRAPS

The four development traps interact and reinforce each other. This makes development challenges particularly complex and the need for sound analytical tools and coordinated policy responses increasingly relevant.

- There are many examples of how the traps are mutually reinforcing. With respect to the social vulnerability and productivity traps, the vulnerability associated with informal jobs is largely a by-product of low levels of productivity that characterize the Indian economy.

- Meanwhile, informality itself acts as a strong barrier to increases in productivity and tax revenues.

- Likewise, weak institutions and social vulnerability are mutually reinforcing.

- Populations are vulnerable because they lack an adequate safety net or because weak institutions do not provide them with quality public services such as education and health.

- At the same time, vulnerability weakens the capacity and willingness to pay taxes and comply with formal rules, weakening the institutional setup.

- The productivity trap is also directly linked to institutions, which appear as one of the main determinants of success for countries that overcame this challenge.

- Eventually, the environmental trap is also directly linked to the diversification of the productive structure, and to the ability of the institutional setup to direct investments from resources and carbon-intensive sectors into environmentally efficient technologies.

- At the same time, environmental degradation and depletion reinforce the vulnerability trap by increasing the overall level of uncertainty.

THE WAY FORWARD

So Govt budget policy responses to overcome these development traps in India must consider their interactions. Better understanding the links and common causalities between different policy issues and objectives will be critical to developing responses that address their complex interactions effectively.

THE CONCLUSION: Leaving for the future the question of whether growth beyond 2025 can be maintained at a high pace, the question to ask today is whether such growth should be the sole measure of success. What about employment, poverty, the environment, education, and health — all of which have independent but also inter-linked salience, have suffered in the last couple of years, if not longer, and which the Budget seems to underplay?

Spread the Word