THE CONTEXT: The Supreme Court, in July 2022,in Satender Kumar Antil vs Central Bureau of Investigation, recommended the Union Government introduce a special enactment like a “Bail Act” to streamline the grant of bail. The court also gave other directions for making the process of granting bail efficient and effective. This article analyses these developments from the UPSC perspective.

AN OVERVIEW OF THE JUDGMENT OF THE SUPREME COURT

A BAIL ACT

- The Government of India may consider the introduction of a separate enactment in the nature of a Bail Act so as to streamline the grant of bails.

COMPLIANCE WITH CrPC

- The investigating agencies and their officers are duty-bound to comply with the mandate of Section 41 and 41A of the CrPC and the directions issued by this Court in Arnesh Kumar.

- Any dereliction on their part has to be brought to the notice of the higher authorities by the court.

- The courts will have to satisfy themselves on the compliance of Section 41 and 41A of the Code. Any non-compliance would entitle the accused for a grant of bail

FORMULATION OF STANDING ORDERS

- All the State Governments and the Union Territories are directed to facilitate standing orders for the procedure to be followed under Sections 41 and 41A of the Code

ARREST AS A LAST RESORT

- There needs to be strict compliance with the mandate laid down in the judgment of this court in Siddharth(in which it was held that investigating officers need not arrest each and every accused at the time of filing the charge sheet).

CREATION OF SPECIAL COURTS

- The State and Central Governments will have to comply with the directions issued by this Court from time to time with respect to the constitution of special courts. The High Court in consultation with the State Governments will have to undertake an exercise on the need for special courts. The vacancies in the position of Presiding Officers of the special courts will have to be filled up expeditiously.

RELEASE OF UNDERTRIALS

- The High Courts are directed to undertake the exercise of finding out the undertrial prisoners who are not able to comply with the bail conditions. After doing so, appropriate action will have to be taken in light of Section 440 of the Code, facilitating the release.

- An exercise will have to be done in a similar manner to comply with the mandate of Section 436A of the Code both at the district judiciary level and the High Court as earlier directed by this Court in Bhim Singh.

TIME-BOUND DISPOSAL OF BAIL APPLICATION

- Bail applications ought to be disposed of within a period of two weeks and applications for anticipatory bail are expected to be disposed of within a period of six weeks.

REPORT ON CONFORMITY

- All State Governments, Union Territories and High Courts are directed to file affidavits/ status reports within a period of four months.

WHAT IS A BAIL AND WHAT ARE ITS TYPES?

A Bail denotes the provisional release of an accused in a criminal case in which court the trial is pending and the Court is yet to announce judgement. The term ‘bail’ means the security that is deposited in order to secure the release of the accused. There are 3 types of bail Regular, Interim and Anticipatory.

- Regular bail- A regular bail is generally granted to a person who has been arrested or is in police custody. 2005 amendment to the CrPC abolished sureties in the case of indigent(poor) people.

- Interim bail- This type of bail is granted for a short period of time and it is granted before the hearing for the grant of regular bail or anticipatory bail.

- Anticipatory bail- Anticipatory bail is granted under section 438 of CrPC either by session court or High Court. An application for the grant of anticipatory bail can be filed by the person who discerns that he may be arrested by the police for a non-bailable offence.

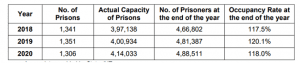

THE PRISON STATISTICS INDIA–2020- NATIONAL CRIME RECORDS BUREAU (NCRB).

- The increase in the share of under-trials in prisons was at an all-time high. PSI 2020 puts the percentage at 76% in December 2020: An increase from the earlier 69% in December 2019. The people who are undertrials are those yet to be found guilty of the crimes they have been accused of. In 17 states, on average, prison populations rose by 23% from 2019 to 2021, as opposed to 2-4% in previous years.

- The appalling figures come from states such as Uttar Pradesh, Sikkim, and Uttarakhand,which had tragic occupancy rates of 177%, 174%, and 169%, respectively (December 2020).

- Only Kerala(110% to 83%), Punjab (103% to 78%), Haryana (106% to 95%) Karnataka (101% to 98%), Arunachal Pradesh (106% to 76%) and Mizoram (106% to 65%) could reduce their occupancy of prisons below 100%.

BAILABLE OFFENCE AND NON-BAILABLE OFFENCE

The Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 talks in detail about the bail process and how it has to be obtained. However, it does not define bail. Section 2(a) Cr.P.C. says that a bailable offence means an offence which is shown as bailable in the First Schedule or which is made bailable by any other law for the time being in force, and a non-bailable offence means any other offence. The Code of Criminal Procedure deals with various provisions as to bail and bonds. It lays down when bail is the right of the accused, when bail is the discretion of the Court, in what circumstances said discretion can be exercised, what are the terms and conditions which would be required to be observed by the accused, who has been released on bail and what powers are vested in the Court in the event of accused committing default of bail order etc.

WHY THERE IS A TENDENCY TO DENY BAIL?

Motivated arrest often leads to denial of bail and mechanical remand by the subordinate judiciary. Due to the concept of pecuniary ‘surety’, the archaic Indian law on bail already had a class character wherein, for the rich, bail is the rule and for the poor, invariably, jail. Justice Krishna Iyer in the Moti Ram case where a poor labourer was asked for a surety of Rs 10,000 in 1978 was pained to observe that “the poor are priced out of their liberty in the justice market.” Lately, it would appear that religion is a new class.It has been seen that many times, particularly when either the cases are controversial or delicate or political in nature or where there can be an outburst, the tendency in the lower courts is why should we do it, let the person take it from the high court or Supreme Court.”A tendency among government agencies to hand over documents in sealed covers to courts in “every case” coupled with an inclination among judges to verbatim reproduce their contents as judicial findings also lead to denial of bail. In non-bailable offences, bail is discretionary and there are conditions that the judge may impose which are selectively applied many times. Also, there are special penal laws like the UAPA, PMLA etc where some overzealous SC judges have given a free pass to the executive.

IMPLICATIONS OF DENIAL OF BAIL

- Violation of the principle “bail is the rule, jail is the exception

- The rights of the citizens are unjustifiably curtailed

- Overcrowding of prisons and increase in state expense

- Inefficiency in the criminal justice system

- Scope for rent-seeking, corruption at multiple levels

- Productivity of the individual is lost

- Social stigma and long incarceration

- The process becomes the punishment

- Chances for reformation and rehabilitation reduce.

HOW CAN A SEPARATE BAIL LAW ADDRESS THE SITUATION?

CrPC IS ESSENTIALLY COLONIAL

- Notwithstanding subsequent revisions, the CrPC essentially retains its initial form as drafted by a colonial power over its subjects.

- The Code does not see the arrest as a fundamental liberty concern.

UNIFORMITY AND CERTAINTY

- “The cornerstones of judicial dispensation are uniformity and predictability in court decisions.” Persons accused of the same offence shall not be treated differently by the same court or by separate courts.

INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCE

- In the United Kingdom and many states in the United States, there are specific laws that lay down guidelines for arrests and grants of bail. There is a “pressing need” for a similar law in India.

DEDICATED LEGAL REGIME

- several previous judgments and guidelines regarding bail and the numerous conditions that need to be complied with while arresting an accused are often not followed.

- So a new bail law will integrate these aspects and provide a cohesive form which can be a shot in the arm for personal liberty.

THE BAIL ACT OF THE UNITED KINGDOM

The Bail Act of the United Kingdom of 1976 governs the process of granting bail. One distinguishing element is that one of the legislation’s goals is to “reduce the size of the convict population.” The statute also includes procedures for defendants to receive legal representation. The Act recognises a “general right” to bail. Section 4(1) establishes the presumption of bail by declaring that the legislation applies to a person who shall be granted bail unless otherwise provided for in Schedule 1 to the Act.

In order to reject bail, the prosecution must demonstrate that there are reasonable grounds to believe the defendant on bail will not surrender to custody, will commit an offence while on bail, will interfere with witnesses, or will otherwise obstruct the course of justice;

WHETHER INDIA NEEDS A SEPARATE BAIL LAW?

LAW COMMISSION REPORT

- When the Department of Legal Affairs asked the Law Commission about the need for a separate bail law in India in 2015, the commission concluded that it wasn’t required.

IMPUNITY FOR OFFICERS STILL EXIST

- The problem is not a lack of guidelines but the fact that there are no consequences for officials who violate them.

- There is a belief that officers can get away with not following the law.

- The authorities follow the procedure “as per their wish”. A new Bail Act is unlikely to change the situation.

DOES NOT ADDRESS THE ROOT CAUSE

- Laws dealing with criminal activity provide high scope for police discretion, especially in cognizable offences. For instance Section 124A of IPC deals

- with sedition(before the SC judgment on sedition) and Section 153A is related to promoting enmity between groups. Also, the vague and overarching terms in laws like UAPA, IT Act

- 2000, etc provide huge scope for abuse of these laws by police. In PUCL Vs. Union of India, 2021, the Supreme Court felt appalled after finding that

- people are still being booked and tried under Section 66A of the Information Technology Act.

THE EXECUTIVE IS AN INTERESTED PARTY

- The judiciary is better placed to deal with issues of bail instead of the government. The law made by “the state may have the potential to introduce caveats on the law of bail,” which in effect create more problems than they purport to solve.

DISCRETION OF THE JUDGES CAN’T BE CODIFIED

- The enormity of the charge, nature of the accusation, severity of punishment on conviction, possibility of the accused absconding if released on bail, the danger of witnesses being tampered with, health, age and sex of the accused etc. are the crucial grounds for deciding the bail which can’t be measured through a straightjacket mathematical formula.

- Discretion will always create a chance for rent-seeking and biased decisions of the judges, even in the presence of bail law.

THE WAY FORWARD:

- A Bail Act in the line of the developed democracies can be enacted after a wide-ranging consultation although it in itself is not a panacea for the problem of denial of bail.

- The judicial discretion in granting bail needs to be circumscribed and cannot be used in an arbitrary manner; sound discretion is guided by law and governed by rule and by the whims and fancies of the judge. The subordinate judiciary and the High Courts need to be sensitized and taken to task for rejecting bail on sterile and irrelevant grounds and also for imposing onerous bail conditions.

- According to 21st Law Commission, Confinement is detrimental to the person accused of an offence who is kept in custody, imposes an unproductive burden on the state, and can have an adverse impact on future criminal behaviour, and its reformative perspectives will stand diminished. Hence, the bail should not be denied unless there are compelling circumstances.

- The problem of delays in deciding bail applications can be reduced by utilizing e-governance, and AI and also by improving the infrastructure base of the district judiciary through the establishment of a National Judicial Infrastructure Corporation.

- The process of arrest by the police and other investigative agencies needs to be strictly in accordance with the laws and directions of the SC. Exemplary punishment needs to be awarded for violation

- Legal education and awareness of the legal system and legal aid is the need of the hour and the Legal Services Authorities need to take concrete steps in this regard.

- A comprehensive reform in the entire criminal justice system is required to address the root causes and the Malimath Committee report provides a goldmine of suggestions in this regard.

THE CONCLUSION: As per the NCRB data around 76 per cent of inmates in the prison are undertrials who are mainly booked for non-heinous crimes and the major reason for such a state of affairs is the poor bail system in the country. The SC directions and recommendation for a separate bail law have come as a fresh lease of life, but without a comprehensive overhauling of the criminal justice system, these measures may not have the desired impact.

QUESTIONS TO PONDER

- Critically examine the need for a separate Bail Law in India.

- What are the implications of the denial of bail in deserving cases? How far do you think that a separate bail law can actually implement the principle “ bail is the rule, jail is the exception” on the ground?