THE CONTEXT: Recent visits by Foreign Secretary Harsh Vardhan Shringla and National Security Adviser Ajit Doval to countries in the region appear to show new energy in India’s neighbourhood policy. This article discusses the need for the reworking of neighbourhood policy.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF INDIA’S REGIONAL POLICY

- The notion of regional primacy certainly persisted in the Nehruvian era —seen in the three security treaties that the first prime minister signed with Bhutan, Sikkim and Nepal during 1949-50.

- The post-colonial phase, which broadly began in the late 1940s, again, has had a complementariness that helped India and its neighbours to propel ideas such as non-alignment in the international arena, which was inspired by a macro-level “third worldism”, “South-South cooperation” and so on.

- As India got involved in border conflicts with Pakistan & China and also due to persisting poor economic policies, its influence in the neighbourhood got marginalised.

- Though multilateralism prevailed in India’s foreign policy at the international level, there has been a tremendous focus on bilateralism in India’s approach to its immediate neighbourhood.

- India’s economic reorientation since 1991 and the rediscovery of regionalism did open possibilities for reconnecting with its neighbors.

In that context, to a large extent, India’s foreign policy approach towards its neighbours was shaped by the “principle of balancing”.

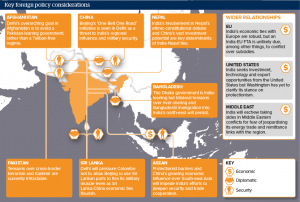

KEY FOREIGN POLICY CONSIDERATIONS

NEED FOR POLICY REWORK

It is extremely important that our engagement with our neighbouring countries should not be event-oriented; it should be process-oriented. And we should have a plan for a continuous engagement at various levels.

- Recently, there have been many strains in ties with neighbours. For instance, With Nepal over its Constitution in 2015 and now over the map, and With Bangladesh over the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA).

- Need clarity regarding China. It is very easy to accuse any of India’s neighbouring countries of being too close to China. But it’s very difficult to set out the exact terms of what they should or shouldn’t do with China.

- South-East Asia is one of the largest regions in the world by population. It is one of the least integrated regions with tremendous deficits in terms of infrastructure, connectivity, and interdependence. It is a region that is now being exposed to various geopolitical competition dynamics.

- We should focus on creating interdependence in this region that will give India strategic leverage.

There should be an awareness that there is a price to be paid if we try to always prioritize domestic factors over foreign policy issues. Generosity and firmness must go hand in hand. If you have determined what your key interests are, then it is better to make it known what the red lines are.

CHALLENGES

Structural Challenges: India has historical legacies of border conflict, ethnic and social tensions and India’s are the dominant structural handicaps working against the success of India’s policy in South Asia.

- The challenges of settling boundaries, sharing river waters, protecting the rights of minorities, and easing the flow of goods and people, affects regional diplomacy.

- For example, the issues related to Madhesis in Nepal, Tamils in Sri Lanka, border and river water disputes with Bangladesh are accorded to various structural handicaps of India.

Lack of Consensus on Security and Development:

- South Asia is one of the only regions without any regional security architecture.

- India’s big brotherly stature has been seen as more of a threat by other countries of the region rather than an enabling factor to cooperate for the security and development of the region.

Chinese influence: Beyond the bilateral territorial dispute between India and China, the emergence of a powerful state on India’s frontiers affected India’s relationship with its neighboring countries.

- China has made foray into India’s neighbourhood of alternative trade and connectivity options after the 2015 India-Nepal border blockade (e.g. highway to Lhasa, cross-border railway lines to the development of dry port).

- In Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, the Maldives and Pakistan, China holds strategic real estate and has a stake in their domestic policies.

- China is undertaking political mediations such as stepping in to negotiate a Rohingya refugee return agreement between Myanmar and Bangladesh, hosting a meeting of Afghanistan and Pakistan’s foreign ministers to bring both on board with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and is also mediating between Maldivian government and opposition.

India’s Hard Power Tactics:

- India has a central location in South Asia and being the largest geographically and economically, India should be expected to hold greater sway over each of its neighbours but many of its hard power tactics do not seem to work.

- The 2015 Nepal blockade and a subsequent cut in Indian aid did not force the Nepali government to amend its constitution as intended and may have led to the reversal of India’s influence there.

Political loggerheads:

- For various reasons other governments in the SAARC region are either not on ideal terms with India or facing political headwinds.

- In the Maldives, President Yameen Abdul Gayoom has challenged India through its crackdown on the opposition, invitations to China and breaking with India’s effort to isolate Pakistan at SAARC.

- In Nepal, the K.P. Sharma Oli government is not India’s first choice, and both countries have disagreements over the Nepalese constitution, Treaty of Peace and Friendship 1950 etc.

- In Sri Lanka and Afghanistan, where relations have been comparatively better for the past few years, upcoming elections could pose a challenge for India.

WHAT SHOULD BE DONE

Many of these factors mentioned are hard to reverse but the fundamental facts of geography and shared cultures in South Asia are also undeniable, and India must focus its efforts on “Making the Neighbourhood First Again”

1. Soft Power:

- Despite the apparent benefits of hard power and realpolitik, India’s most potent tool is its soft power.

- Its successes in Bhutan and Afghanistan, for example, have primarily been due to its development assistance than its defence assistance.

- Considering this India’s allocations for South Asia have also increased by 6% in 2018 after two years of decline.

2. Approach towards China: Instead of opposing every project by China in the region, India must attempt a three-pronged approach:

- First, where possible, India should collaborate with China in the manner it has over the Bangladesh China-India-Myanmar (BCIM) Economic corridor.

- Second, when it feels a project is a threat to its interests, India should make a counter-offer to the project, if necessary, in collaboration with its Quadrilateral partners, Japan, the U.S. and Australia. Third, India should coexist with projects that do not necessitate intervention, while formulating a set of South Asian principles for sustainable development assistance that can be used across the region.

3. Learn from ASEAN:

- Like ASEAN, SAARC countries must meet more often informally, interfere less in the internal workings of each other’s governments, and that there be more interaction at every level of government.

- Further, some experts have argued that like Indonesia India too must take a back seat in decision-making, enabling others to build a more harmonious SAARC process.

4. Multi-vector foreign policy:

- Promotion of a multi-vector foreign policy by diversifying its foreign policy attention on multiple powers (not only the US; but also Russia, the European Union, Africa and so on) in the global arena while developing a stronger matrix of multilateralism and employing stronger diplomatic communications strategies.

5. Understand limitations of the neighbourhood first:

- India needs investments, access to technology, fulfilment of its defence and energy needs and defends of its interests in international trade negotiations, besides seeking reform of the international financial and political institutions to obtain its rightful say in global governance which may not be fulfilled by its neighbours.

Proximity is one of the greatest assets which we have with respect to all our neighbors. But this connectivity has to be linked with the ‘software of connectivity’.

WAY FORWARD:

A new neighborhood policy needs to be imaginatively crafted in tune with the emerging realities in order to maintain its regional power status and to realize status transformation to the next level in the near future. Such re-strategizing can enable India to strengthen its position in the region/neighborhood.

- India’s neighborhood policy can go a long way if these initiatives are properly backed up by sufficient innovative hard power resources (defense and economy) and the use of soft power strategies.

- Soft power strategies can be operationalized only by way of creatively propelling India’s democratic values and ideas, which can further improve its civilizational ties with regional states. This in turn can lead to a recalibration of India’s neighbourhood policy.

- India’s neighborhood policy should be based on the principles of the Gujral Doctrine. This would ensure India’s stature and strength cannot be isolated from the quality of its relations with its neighbors and there can be regional growth as well.

The China factor, the changing global power architecture, and the existing conflicts with neighbours will play a significant role in India’s foreign policy, of which its neighbourhood policy is a crucial one.

CONCLUSION:

There is no doubt that the challenges which India must deal with in its neighborhood will become more complex and even threatening compared to two decades ago. But neighborhood first policy must be anchored in the sustained engagement at all levels of the political and people to people levels, building upon the deep cultural affinities which are unique to India’s relations with its neighbors.

Spread the Word