THE CONTEXT: The Covid-19 pandemic and its eventful aftermath has been inflicting unprecedented stress, on the already vulnerable Indian society. Most have seen their incomes fall, many have seen their families uprooted, some have even lost their lives. On moral grounds alone, there is a strong case for augmenting spending on social protection for the poor.

STATUS OF SOCIAL PROTECTION IN INDIA

- Prior to COVID-19, despite absolute poverty reduction in the past two decades, half of India’s population was vulnerable with consumption levels precariously close to the poverty line.

- Ninety percent of the Indian workforce is informal, without access to significant savings or work-place based social protection benefits such as paid sick leave or social insurance.

- The Periodic Labour Force Survey (2017-18) has found that only 47% of urban workers have regular, salaried jobs.

- Even among workers in formal employment, over 70% do not have contracts, 54% are not entitled to paid sick leave and 49% do not have any form of social security benefits. These workers, who may not be identified as ‘poor’ as per the consumption data but are at grave risk of falling into poverty due to wage and livelihood losses triggered by shrinking economic activity.

- In India, the pandemic has brought to the forefront the chronic poverty and inequality that already plague the nation, where more than 21.9% of the population lives below the poverty line. The implementation of nationwide lockdown measures has caused factories to shut down and interrupted supply chains, rendering migrants and non-migrant employees jobless.

SOCIAL SECURITY

- According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), Social Security is a comprehensive approach designed to prevent deprivation, give assurance to the individual of a basic minimum income for himself and his dependents and protect the individual from any uncertainties.

- It is also comprised of two elements, namely:

- Right to a Standard of Living is adequate for health and well-being, including food, clothing, housing, medical care, and necessary social services.

- Right to Income Security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age, or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond any person’s control.

- In a report on the state of social protection globally, the UN’s International Labour Organization said that 4.1 billion people were living without any social safety net of any kind. Social protection includes access to health care and income security measures related especially to old age, unemployment, sickness, disability, work injury, maternity, or the loss of the main breadwinner in a family, as well as extra support for families with children.

CHALLENGES IN DELIVERING ENTITLEMENTS AT SCALE

- The limiting factors: Even before the pandemic, the effective and smooth distribution of social protection benefits has been hampered by barriers such as insufficient staffing, funding, and training of local-level government bodies and organizations (including SHGs and NGOs).

- Reaching the last mile: Common Service Centres (or CSCs) that are front-end channels for delivering services at the last mile have their fair share of problems, associated with weak connectivity, poor infrastructure, minimal incentives, and a lack of automated backend processes.

- Ever-increasing job loss: People cannot carry on with their usual jobs or occupations. The existing situation of unemployment worsens. Incomes fall or cease. Economically better-off people manage with varying degrees of difficulty, but people from the lower economic sections become almost destitute.

- Distribution struggles: Amidst free distribution of food and essential items to the needy and poor, people were seen fighting amongst themselves in the race to get there first and even to the extent of snatching it from others. Members of the NGOs and social organizations engaged in community service during these times were also hackled and abused.

- Targeting errors: While the JAM trinity and the increasing reliance on Direct Benefit Transfers have been a step towards automating the existing structure, the reform has its own shortcomings. For example, the Aadhaar-Based Biometric Authentication at Fair Price Shops often fails to read fingerprints of the elderly and those engaged in manual work as demonstrated in Karnataka, Gujarat, and Rajasthan. Targeting is a key issue to consider when designing inclusive social assistance programs in developing countries with large populations. In India, PDS beneficiaries are bracketed on the basis of a poverty line that may not reflect the accurate socio-economic status of a household.

GOI’S RESPONSE TOWARDS SOCIAL PROTECTION

- Introducing financial cushion: The Government of India and the World Bank today signed a $750 million of $1 billion proposed for Accelerating India’s COVID-19 Social Protection Response Programme to support India’s efforts at providing social assistance to the poor and vulnerable households, severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

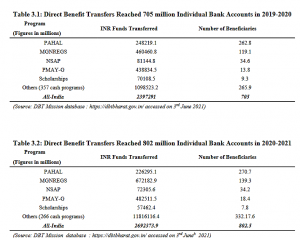

- The first phase of the operation will be implemented countrywide through the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana (PMGKY). It will immediately help scale-up cash transfers and food benefits, using a core set of pre-existing national platforms and programs like the following:

- Both anticipation of benefit payments and a top-up of INR2,000 to beneficiaries of PM-Kisan, a cash transfer scheme supplementing farmers’ income and supporting agriculture-related expenses

- An increase of INR20 in the daily wages of workers registered under Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), the flagship public works program, representing up to INR2,000 per worker per year.

- Expansion of the Public Distribution System (PDS) to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19, with beneficiaries of Antyodaya Anna Yojana, a program providing highly subsidized food grains, receiving free food, and additional food subsidies to mitigate food insecurity during the pandemic.

- Government payment of three months’ worth of provident fund contributions for employees who earn less than INR15,000 per month and work in companies with less than 100 employees in which 90 percent of employees’ wages are below the INR15,000 threshold.

- Financial support for 23 million construction workers from the Building and Construction Workers’ Fund managed by state governments, with a one-time cash benefit ranging between INR1,000 and INR5,000.

- Schemes such as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), public distribution system (PDS), and a modest universal income transfer can drive growth by boosting demand, correcting market failures, improving credit access, and providing the insurance needed for people to undertake risky investments to improve productivity. The GOI thus increased budget grants for these schemes. The sub-schemes like ‘One Nation, One Ration Card’ further amplify the penetrative potential of schemes like PDS.

In the second phase, the program will deepen the social protection package, whereby additional cash and in-kind benefits based on local needs will be extended through state governments and portable social protection delivery systems.

Analysis by World Bank Group

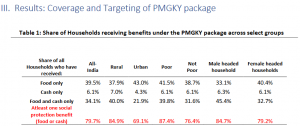

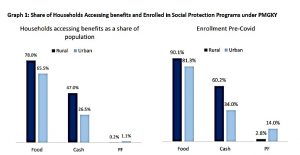

Coverage and outreach of the first round of India’s social protection response have been impressive at scale, reaching a majority of households. Between May and August 2020, more than 87 percent of India’s poorest households reported receiving at least one benefit, food or cash, under the PMGKY. Across the country, nearly 74% of all households received food through PDS allocations, 40% of households received cash transfers.

IMPROVING TARGETING OF SOCIAL WELFARE: FILLING THE LOOPHOLES

Shifting priorities and erring on the side of being inclusive, i.e., recognizing the scale of the economic losses that the population faces and focusing on plugging exclusion errors that deny benefits to eligible beneficiaries.

- Moving towards self-targeting: Various stakeholders argued that there is a need to tailor the economic response to COVID-19 to the public health response. For instance, during intense lockdown periods where economic activity is severely curtailed, more universal and broad transfers are needed. Direct food assistance can be particularly useful in this scenario since they allow for self-targeting.

- Avoiding one-size-fits-all approach: While monitoring attendance using Aadhaar authentication has already been discontinued for central government employees for fear of virus transmission, this should be employed as a long-term solution for beneficiaries as well. Rather than relying entirely on ABBA (Aadhaar Based Biometric Authentication) transactions, recording transactions in offline mode where needed would prevent their exclusion.

- To mitigate the health risks of crowding in PDS centers, in-kind transfers can also be made through other means like door-step delivery through PDS trucks.

- Community model of social security: Organizations at the community level, like NGOs, CSOs, and Self Help Groups (SHGs) are also making efforts to reach beneficiaries, spread information, and mobilize relief measures. In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, SHGs have worked to circulate relevant health information using WhatsApp groups.

- A study conducted by Gram Vaani found that when community volunteers intervened in escalating complaints about public schemes, there was an improved turnover in response from administrators.

- Utilizing last-mile agents to increase the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of social assistance programs can be considered as well. According to the Business Correspondents Federation of India, 80-85% of BCs were active as of June 2020. These agents have played a vital role in ensuring last-mile access to Direct Benefit Transfers under the PMGKY.

- Using technology augmentation: Existing government service delivery systems like HESPL’s Haqdarshak and DEF’s Mera App rely on an ‘agent + technology’ model to overcome the barriers of financial and digital illiteracy. While agent involvement has been critical for enabling cash withdrawal, the COVID-19 experience has highlighted how this model may benefit from the development of simplified applications that enable self-service.

Successful Social security models

In practice, by relaxing the criteria of having a specific type of bank account, targeting can be made more universal; Tamil Nadu has disbursed cash and ration-based commodities to ration card owners. The utilization of a job card (MNREGA) can also be considered to make targeting more inclusive.

THE WAY FORWARD

- While the government has responded to the challenges posed by COVID-19 through different interventions, the country could benefit from taking further steps to ensure universal social protection coverage, including the ‘missing middle.

- Potential policy strategies encompass the implementation of a universal child benefit, which would ensure that all households with children are able to meet their basic needs, and/or greater coverage and adequacy for India’s elderly population through an old-age pension scheme, including through the existing Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme.

- Existing social insurance schemes administered by the Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation should be supported and strengthened to provide social insurance to workers in times of need.

- Furthermore, to guarantee greater coverage for future shocks, flagship programs such as the PDS and MGNREGA could be expanded to provide security to all regions and to households in both urban and rural areas. Lastly, more needs to be done to reach and support internal migrant workers who are either temporarily or indefinitely living outside their home states and often lack access to social protection programs.

- The current ‘one-size-fits-all’ model of national programs which offer the same benefit levels and interventions across a variety of states needs reform. India can draw from the experience of other middle-income countries and allow greater funds and flexibility to sub-national governments to design localized approaches, while retaining a core set of national programs such as MGNREGS, NSAP, PMAY, PAHAL, PDS, and social insurance schemes to operate pan-nationally.

THE CONCLUSION: Debates around reducing the stringency of poverty tests, expanding social assistance programs to cover a wider range of citizens, and improving the ease of receiving benefits all point to the need of developing a more inclusive system of welfare support. To this end, the COVID-19 pandemic can act as an impetus to address the inadequacies of existing mechanisms and institutions and adapt them to not only suit the current situation but also prove resilient in the future.

As India designs its social protection response to the pandemic, the country stands poised for a fundamental transformation from a set of fragmented schemes to an integrated and decentralized system. A broader social protection framework for a more urban, middle-income, mobile, natural disaster-prone, diverse and decentralized India is urgently required.

Spread the Word