THE CONTEXT: Three decades ago, India embarked on a new economic journey when Manmohan Singh, then Finance Minister, placed the reform Bill and echoed Victor Hugo, “No power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come,” in Parliament. Since then, the crisis-hit economy has come a long way and marked its firm presence in the global platform. In this article, we will analyse India’s Journey in these three decades.

AN INTRODUCTION OF THE ECONOMIC REFORMS

- Economic reforms in India refer to the structural adjustments initiated in 1991 to liberalise the economy and accelerate its economic growth rate. The Narsimha Rao Government, in 1991, introduced economic reforms to restore internal and external confidence in the Indian economy.

- The reforms aimed at bringing in greater participation of the private sector in the growth process of the Indian economy. Policy changes were introduced with respect to industrial licensing, technology up-gradation, removal of restrictions on the private sector, foreign investments, and foreign trade.

- The reforms aimed to attain a high rate of economic growth, reduce the rate of inflation, reduce the current account deficit, and overcome the balance of payments crisis. The important features of the economic reforms were Liberalisation, Privatisation and Globalisation, popularly known as LPG.

NEED FOR ECONOMIC REFORMS

The need for the introduction of the reforms was because of the following factors:

POOR PERFORMANCE OF THE INDUSTRIAL SECTOR

Before the introduction of economic reforms, the industrial sector suffered due to bureaucratic controls. The industries had to obtain several licenses and permissions for any undertaking activity such as setting up a new firm, starting a new product line, expanding existing business, foreign investments, etc. Many public sector enterprises were incurring huge losses due to poor productivity.

The main objectives of the industrial policy introduced in 1991 were:

I. To unshackle the Indian industrial sector from the cobwebs of unscrupulous bureaucratic controls.

II. To introduce liberalisation to integrate the Indian economy with the world economy.

III. To remove restrictions on foreign investments and relieve the entrepreneurs from the restrictions of the MRTP Act.

IV. To shed the load of public enterprises that were incurring heavy losses.

ADVERSE BALANCE OF PAYMENTS

- India faced a severe economic crisis during the end of the 1980s. India was unable to meet its international debt obligations and was pushed to a situation of near bankruptcy.

- The foreign exchange reserves were insufficient to pay the import bills. The Balance of Payments deficit could not be financed beyond a certain point.

Some of the factors responsible for the crisis were:

I. The rising level of expenditure over revenue.

II. Heavy government borrowing.

III. Inefficient utilisation of resources.

IV. Excessive protection to domestic industries.

V. Inefficient management of public sector enterprises.

VI. Lack of technological development and innovation

VII. Lack of investments in research and development.

RISE IN FISCAL DEFICIT

- This was mainly due to the increase in the non-developmental expenditure of the government. The government had to borrow a huge sum of money to finance the deficit and meet these debts’ interest obligations.

- The government was in a debt trap. Thus, there was a need to bring in reforms to reduce the non-developmental expenditure and to bring about a fiscal discipline.

INFLATION

- Due to continuous borrowing by the government to meet its mounting expenditure, there was a rapid increase in the money supply.

- The government resorted to deficit financing wherein the RBI financed the borrowings by the Government of India by printing currency notes.

- This leads to a rise in the money supply. When the money supply increased, the demand for goods and services also rose, increasing their prices and causing an inflationary situation.

THE GULF WAR

- The Gulf war during 1990-91 had a significant impact on the supply of oil. As a result, the price of oil shot up, increasing India’s foreign currency outlays. The Gulf crisis also affected the flow of foreign currency into India.

- The NRI deposits were moving out of India and remittances from Indians employed abroad were also affected during the war.

THE ECONOMIC REFORMS

Economic reforms in India were implemented to change the pattern of economic activities to liberalise the Indian economy and accelerate the rate of economic growth. These new economic reforms brought about a structural change in the share of different sectors in the national income.

The new economic reform policies mainly focused on structural reforms in the agricultural sector, industrial sector, financial sector, and global trade. Such economic reforms were possible with the help of broad and comprehensive policies on liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation.

LIBERALISATION – MEANING AND FEATURES

The main objective of liberalisation was to unshackle the industrial sector from the cobwebs of unnecessary bureaucratic controls.

The main features of liberalisation policy were

ABOLITION OF INDUSTRIAL LICENSING

- The new industrial policy of 1991 abolished the industrial licensing for all the industries except for a selected 18 industries due to security and strategic concerns.

REMOVAL OF RESTRICTIONS

- Other than those 18, all industries could set up and sell shares without any restrictions; they could expand their business and start a new product line without obtaining any license.

RELAXATION OF MRTP RESTRICTIONS

- The Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices (MRTP) Act aimed at controlling monopoly practices to prevent concentration of economic power.

- The MRTP Act has now been replaced by the Competition Act, 2002, which came into effect in 2009. The Competition Act checks all anti-competitive practices and prohibits abuse of dominance. To protect consumer interest at large, it aims at promoting and sustaining competition in the market.

FOREIGN INVESTMENT

- The reforms reduced several procedural bottlenecks for foreign investments. Approval was given for foreign direct investment up to 51 percent of the equity in high priority industries.

FOREIGN TECHNOLOGY

- Automatic approval was provided to Indian industries with respect to foreign technology agreements, especially in the case of high priority industries.

- Permissions were not required for hiring foreign technicians and experts and for foreign testing of indigenously developed technologies.

GLOBALISATION – MEANING AND FEATURES:

Globalisation may be defined as the integration of the domestic economy with the world economy to facilitate the free movement of goods, services, people, ideas, technology, etc. It refers to the opening of the economy to international competition.

The major features of globalisation measures as undertaken in 1991 were:

Reduction of Trade Barriers

- With the introduction of globalisation measures, trade barriers restrictions were reduced.

- It provided immense opportunities to Indian industries to expand their markets abroad and offered Indian consumers a wide variety of quality goods at competitive prices.

- The export-import policy announced for the period 1992-97 removed all restrictions on external trade and enhanced the export capabilities of the Indian industries.

Promotion of Foreign Direct Investment:

- Many Indian industries were opened to foreign direct investment.

- India became a favourable investment destination for foreign investors due to the low cost of production and availability of cheap labour resources.

- The government of India further initiated a series of measures to promote foreign technical collaborations in case of high priority industries and for the import of foreign technology. Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB) was set up to facilitate foreign direct investments in India.

To Encourage Efficiency

- Globalisation encouraged domestic industries to become more competitive and efficient to face competition at the global level.

- The domestic industries had to produce quality goods at low cost to compete with the foreign producers’ cheaper and superior quality goods.

Diffusion of Technology

- An opportunity to India to have access to global technology and India could utilise the technologies of developed countries without many investments in research and development.

PRIVATISATION-MEANING AND FEATURES:

Privatisation refers to the introduction of private ownership in public sector enterprises. The government holding in public sector enterprises was sold to increase private participation.

Many public-sector units were incurring losses due to inefficiencies in management and lack of innovation and investments in research and development. Privatisation measures enabled modern technology, improved the quality of service, and led to efficient utilisation of resources.

Various privatisation measures introduced in India included:

- Transfer of ownership of public sector units, either fully or partly, to private hands through denationalisation.

- Transfer of control to the private sector through disinvestment policies.

- Opening of areas that were exclusively reserved for public sector.

- Transfer of management to the private sector through franchising, contracting, and leasing.

- Limiting the scope of the public sector.

The privatisation wave in India, which was a part of the economic reforms of 1991, increased the role of the private sector and restricted the public sector to priority areas which included:

- Physical and social infrastructure

- Mining and oil exploration

- Manufacture of products that were of strategic importance and where security concerns were involved like in the case of manufacture of defence equipment, and

- Investments in technologies that required huge outlay and where private sector investment was inadequate.

Privatisation measures were introduced in India as part of the economic reforms in 1991 for the following reasons:

To Reduce the Burden of the Government

- Many public sector units were only functioning to protect the interests of the laborers. Privatisation offloaded this burden from the government and reduced the strain on resources.

To Promote Efficiency

- Many public sector companies were also struggling due to inefficient management, lack of transparency and corruptive practices.

- Privatisation measures got rid of these problems and enabled the public sector units to achieve optimum productivity.

To Enhance Investment Opportunities

- Privatisation helped in reducing the inconsistencies in management and improved the economic status of many public sector units. This brought in good returns and attracted investments.

To Facilitate Growth of Infrastructure

- Privatisation of industries led to the growth of industrial sector on modern lines. The private enterprises, to provide competitive products and services, initiated and facilitated the improvement of the infrastructure.

To Reduce Unnecessary Bureaucratic Interventions

- Privatisation reduced unnecessary government intervention in the management, thereby giving the private enterprises more autonomy in management and operations. This enhanced their efficiency and profitability.

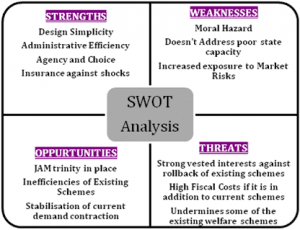

SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF REFORMS: AN ANALYSIS

THE SUCCESS:

SIZE OF GDP AND GROWTH

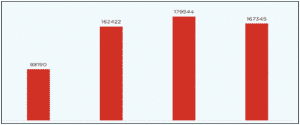

From a GDP of $512.92 billion in 1991, India had grown to $2.70 trillion by 2020. Besides, the average annual growth rates in GDP, post the 1990s, have been around 6.25 per cent against 4.18 per cent for the three decades prior to the reforms.

RATE OF INFLATION

The average annual inflation rates in the post-reform period were significantly lower at around 5 per cent and the gross fiscal deficit was below 4.80 per cent of GDP. While curbing automatic monetisation of deficits and strong monetary measures contributed to lower inflation, disinvestment via privatisation and fiscal restraint in the form of lower subsidies arrested the deficits.

IMPORT- EXPORT

On the external front, the reforms made a significant impact too. Firstly, India’s trade openness increased from a meagre 13 per cent in 1990-91 to 42 per cent in 2020. The exports, driven by the devaluation of the rupee in 1991 and further depreciation in later years, have increased from $17.96 billion in 1990 to $324.43 billion in 2019.

FOREIGN INVESTMENT

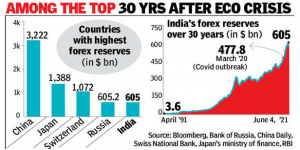

Abolition of licence-raj and curbing of excessive regulations saw rewards in terms of better foreign investment. From $236.69 million in 1991, the net FDI inflows stood at $50.61 billion in 2020. With more foreign companies entering India, domestic consumers benefited from healthy market competition. For Indian manufacturing, the foreign collaborations meant access to technology and, thereby, efficient production. Also, there has been a significant improvement in forex reserves, which are now sufficient to cover 15 months’ imports.

REDUCING POVERTY

The reforms had a telling impact on India’s socio-economic fabric. From about 45 per cent of the population below the national poverty line in 1994, the rates fell to 21.9 per cent in 2011. There have also been improvements in literacy rates, gross enrolments ratio and life expectancy, among others.

AVERAGE MONTHLY PER CAPITA HOUSEHOLD CONSUMPTION EXPENDITURE

It was Rs 243.5 and Rs 370.3 in July-Dec 1991 and this stood at Rs 1,430 and Rs 2,629.7 from July 2011 to June-2012 for rural and urban areas.

FOREIGN EXCHANGE RESERVE

Increased $1.1 billion in 1991 to $642 billion in 2021.

PER CAPITA INCOME

Increased $300.10 to $2200.60 in 2020.

However, opening up the economy makes it susceptible to external shocks. Within a few years after the reforms, the first challenge for India came from its East Asian neighbours in 1997. In a span of three years, the world economy was hit by the dot-com bubble, and the third challenge came in the form of the global financial crisis in 2008. It was prudent economic policies and disciplined financial markets that helped the Indian economy to resist and recover quickly from all three crises.

THE FAILURES:

INCONSISTENT PERFORMANCE

- India’s growth rate and its progression as one of the leading developing economies of the world is inconsistent with the Human Development Index (131st rank in 2020), Global Hunger Index (94th position in 2020), Gender Inequality Index (122nd rank in 2018) and Environmental Performance Index (168th rank in 2020).

RICH-POOR DIVIDE

- It has widened the gap between rich and poor. The World Bank estimates show that the Gini index, a measure of income inequality, had deteriorated marginally from 31.7 in 1993 to 35.7 in 2011.

- According to NSSO consumption surveys, while the bottom 20 per cent of the population contributed to 9.20 per cent of consumption expenditure in 1993-94, their contribution had declined to 8.10 per cent in 2011-12. Further, the share of the top 20 per cent of the population has fattened from 39.70 per cent to 44.70 per cent during the same time.

POVERTY RATE

- As per the Tendulkar Committee estimations, India’s 21.92% of the population was living below the poverty line in 2011-12. However, as per the National Family Health Survey-4 (2015-16), the multi-dimensional poverty rate stood at 27.9%.

- The poverty rate, which was 45% in 1994, declined, especially during 2004-2011 when India implemented substantive anti-poverty measures and rights-based initiatives to uplift the poor.

- This has been affected by the pandemic due to loss of work and earnings and the people, especially informal and daily wage labourers, are pushed into the vicious cycle of poverty.

- A study conducted by the Azim Premji University (2021) finds that “230 million additional individuals slipped below the poverty line defined by the national floor minimum wage” and took away the anti-poverty efforts that were in place during the pandemic for the last 25 years.

UNEMPLOYMENT

- The reduction in poverty rate during 2004-2012 was due to the employment shift from farm to non-farm, especially in the services sector. The construction sector absorbed many informal/unskilled labour resulting in the real wages enhancing the purchasing power of the people.

- On the other side, the number of jobs created during this period was very less, ie, 0.6% per year than the growth of the working-age population.

- According to the International Labour Organization’s ILOSTAT database, India’s unemployment rate in 2020 was the highest since 1991 with 7.11%.

MORTALITY RATE

- Surely economic liberalisation should result in better care for our children, the country has made considerable progress on that front, with the under-five mortality rate coming down from 125.8 per thousand in 1990 to 47.7 per thousand in 2015. But neighbouring Bangladesh and Nepal, much poorer than India, have brought down their under-five mortality rates more than India.

SHARE OF MANUFACTURING IN GDP%

- One would have expected that the New Industrial Policy would have been a pivotal moment for the manufacturing sector and India would soon take its place among the manufacturing powers of East Asia. Still, while, in 1989-90, the share of manufacturing in the gross domestic product was 16.4%, it reduced to 16.2% in 2015-16.

COMBINED FISCAL DEFICIT OF CENTRE AND STATES

- One underlying reason for the crisis of 1991 was the indiscriminate rise in government borrowing in earlier years. It was only to be expected therefore that after the crisis, the government would do all it could to curb its fiscal deficit and that of the states. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen. By 2000-01, the combined fiscal deficit of the centre plus the states, as a percentage of GDP, had risen beyond the 1991 level.

TAX TO GDP RATIO

- One reason why government deficits remained high is that, despite robust economic growth, tax revenues weren’t buoyant. The central government’s gross tax revenues as a percentage of the gross domestic product have remained below the 1991-92 level.

DOES INDIA NEED ANOTHER REFORM?

Successive governments have built on LPG reforms, but a lot more needs to be done if India is to achieve its full potential. A look at the key areas that need urgent intervention to address long-standing issues to help the country achieve double-digit growth.

EDUCATION

- Possibly the most pressing focus area given the urgency to leverage human resources.

- Total revamp from primary level to higher education with equal emphasis on skills.

- Outcome- and learning-based education so that only those eligible progress to the next level.

- Along with health, education should get much higher funding.

HEALTHCARE

- Needs reorganisation and more funding.

- Expensive out-of-pocket health spending major cause of poverty.

- Massive public healthcare supported by insurance for critical care is needed.

JUDICIAL REFORMS

- Inadequate court capacity & judicial delays undermining the economy.

- More courts, better processes, and simpler laws to reduce caseload.

(Vacancies of Judges- 38.70%)

(Pending cases- 63,146 in SC, 56.43 lakh in High Courts and 3.71 Cr in Districts and Subordinate Courts)

TAX REFORMS

- Direct tax reforms progressing as per template.

- GST needs a makeover; all items should be included.

POWER SECTOR

- Unbridled populism has made power expensive, unreliable and inadequate.

- State finances are in disarray in many cases due to power subsidies.

- Users must pay for power; DBT for those states want to support.

- Privatise discoms, enforce open access, continue focus on renewables.

INNOVATION

- Unshackle the startup system totally.

- Provide funding missions for startups in innovation areas crucial to India.

- Encourage blockchain technology in payment systems.

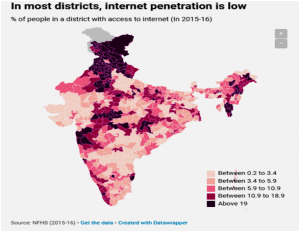

UNIVERSAL BROADBAND

- Reach broadband across the country, keep it affordable.

- Go for satellite broadband in remote areas.

EASE OF DOING BUSINESS

- Much progress made, but the cost of doing business is still high.

- Multiple last-mile hurdles, particularly in the states.

- Massive review of policy, rules and regulations to simplify business.

- Use technology for governance and nonintrusive oversight.

SOME OTHER TARGET AREAS

- Comprehensive social security, which would also make labour reforms easier.

- Steps towards low carbon economy; continued emphasis on EVs and renewables.

- Further relaxation of foreign investment where possible.

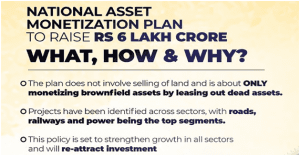

- Massive privatisation to reduce state sector.

- Clear framework to bring back private investment in infrastructure.

- Framework for dispute resolution and enforceability of contracts.

THE WAY FORWARD

- The journey of three decades of economic reforms has certainly transformed our economy from a slow and regulated to a fastened and liberalised path of growth. During this process, what was really missed out was the large workforce of the informal sector. This non-inclusive approach is one of the limitations of the trickle-down economic growth model and needs serious revision.

- The 1991 reforms have provided the required dynamism to the economy. However, it has fallen short in sustaining the pace of growth owing to structural and institutional deficits, including the model of development and centralised governance. 91% of the labour force participation working in the informal sector needs to be provided better avenues of employment by leveraging the inherent potentials of agriculture and allied sectors.

- In spite of the pandemic, the expenditure on the health sector is still low compared with our neighbours like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, which are ahead of India in terms of human development. Social and political (governance) reforms are imperative to achieve the goal of sustainable and equitable economic growth.

THE CONCLUSION: While Covid-19 has been a big blow, the economy was already showing signs of deteriorating growth even in periods preceding the pandemic. This would require immediate intervention to tackle the predicaments of unemployment, poverty, and other social issues. The pandemic has also raised concerns over existing health infrastructure and the future of education. The government must make higher investments in these sectors.

JUST ADD TO YOUR KNOWLEDGE

Disinvestment:

This is one of the most important strategies adopted by the Government of India as a part of its privatisation measures. A disinvestment is an act by which the government sells its complete or a part of its holding in a public sector unit to the private sector.

The disinvestment policies of the government also enable it to raise huge revenue to finance its fiscal deficit. About Rs. 20,000 cores were raised through disinvestment in public sector units between the period of 1991-92 to 2001-02.

The funds raised through disinvestment are also used:

1. To shut down the industries declared sick by the Board of Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR) and settle their claims.

2. To restructure and modernise the public sector enterprises.

3. To settle the public debt.

The disinvestment policies of the government, by bringing in private participation, improve the efficiency of public sector units by lowering their costs of production. It enables access to modern technology, thus, improving the quality of products and services. Disinvestment can be carried out through the public issue of equities to retail investors through Initial Public Offer (IPO).

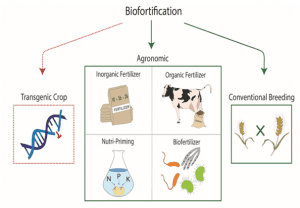

formed from the engineering genes can affect the favouring of one organism. Hence, it can eventually disrupt the natural procedure of gene flow.

formed from the engineering genes can affect the favouring of one organism. Hence, it can eventually disrupt the natural procedure of gene flow.

a biofortified carrot variety with high β-carotene and iron content.(He has been conferred with a National Award by the President of India during Festival of Innovation (FOIN) in 2017 and was also conferred with Padma Shri in 2019 for his extraordinary work in this field).

a biofortified carrot variety with high β-carotene and iron content.(He has been conferred with a National Award by the President of India during Festival of Innovation (FOIN) in 2017 and was also conferred with Padma Shri in 2019 for his extraordinary work in this field).